The project “FishME" (2022–2025) received EUR 275,000 in funding from the FWF and was co-funded by the European Union.

Small fish, big impact

The lake shore is as barren as the high mountain peaks around it, its surface as smooth as glass. But then, suddenly, a trout shoots up to catch a water strider insect on the lake surface. How do you think that fish got to be at this altitude?

That was the question researchers asked 1,318 people online in Austria, Romania, and France. Around two-thirds believed that it was a consequence of human action. The survey was part of the EU research project FishME devoted to investigating how fish introduced by humans affect high mountain lakes and their ecosystems and how quickly these can recover when the creatures are removed.

“Like a canary in a coal mine”

Ruben Sommaruga, a limnologist from the University of Innsbruck, was one of the researchers in FishME. “High mountain lakes,” explains the water expert, “are comparable to canaries in coal mines.” By that he means that these remote lakes are far away from large settlements and therefore, as a rule, not exposed to direct human influence. When researchers do observe changes in the lakes, such as chemical processes occurring in the water, they know that these are due to superregional or global phenomena. One of these phenomena, global warming, is already having a severe impact on the ecosystems of (high) mountain lakes.

Yesterday’s fish, tomorrow’s fish

In addition, humans are increasingly intervening directly in lake ecology by introducing fish to them. In some places, this even happened a long time ago. In the 15th century, the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I asked monks to release fish from the River Danube into Tyrolean high mountain lakes. Some descendants of Atlantic trout (Salmo trutta) still live there now. Around 500 of them are found in Lake Gossenköllesee, at an elevation of roughly 2,400 meters in the Stubai Alps.

Even today, people still release fish, for restaurants or for sport fishing, for instance. Ruben Sommaruga suspects that it was for these reasons that trout have found their way into Lake Timmelsjoch in the Ötztal valley in Tyrol and other high mountain lakes.

FishME

The project applies a multidisciplinary approach to assess fish impacts, pollution interactions, and recovery potential of mountain lakes. The results will be integrated into a socio-ecological Management Toolbox to support evidence-based conservation and guide managers, policymakers, and stakeholders through continuous engagement.

Fish outside their natural habitat

As part of FishME, Ruben Sommaruga and his international colleagues investigated what fish mean for mountain and high mountain lakes in Austria, Italy, Romania, France, and Spain in times of climate crisis. They revisited water and material samples taken over the past 20 years from 101 alpine and high alpine lakes in Austria, Italy, and France. Ruben Sommaruga, his team, and colleagues from the University of Parma also took samples from lakes on the Italian side of the Apennines and in the Austrian Alps. The data showed that fish introduced by humans are already widespread. They were found in 54 of the 101 lakes analyzed, even though most of them were located in protected areas.

Do they belong there?

The researchers also took new samples. Sommaruga and his team analyzed fatty acids, isotopes, and the stomach contents of some of the trout in Lake Gössenköllesee. They showed that the fish fed primarily on bottom-dwelling organisms and zooplankton. A particularly frequent find were the larvae of chironomids.

“Many people think that fish belong in high mountain lakes,” notes Sommaruga. It is mainly ignorance that fuels this idea, however. 332 of the people surveyed in FishME thought that fish stocking was a good measure, 338 did not answer, and 231 said they did not know. The truth, according to Sommaruga, is that fish stocking can have fatal consequences. The feeding habits of the newly introduced fish damage ecosystems in and around the water. If fewer larvae develop into mosquitoes, for instance, they are missing as a food source for birds and reptiles.

The barren lakes are also not an ideal habitat for the fish. “They are poor in nutrients and not very productive. This means that fish populations cannot feed and reproduce at a healthy rate,” explains Sommaruga. He and his team also found young fish in the stomachs of fish of the same species. French colleagues caught fish with severely deformed heads and oversized eyes from high mountain lakes – a consequence of malnutrition.

Black water fleas and green lakes

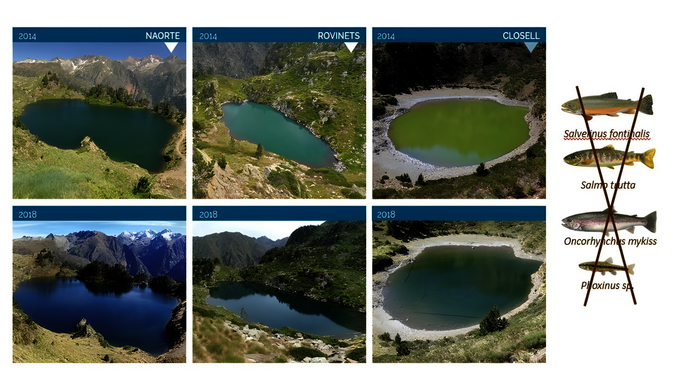

But are all fish the same? The researchers compared the effects in the 54 lakes populated with fish and discovered that in those where minnows (Phoxinus phoxinus) or char are present, native species are declining more rapidly than in those where trout were found. “Minnows are the worst fish species to be introduced into these lakes,” says Ruben Sommaruga. Often used as fishing bait, these small fish eat large quantities of animal plankton such as water fleas.

These organisms, in turn, feed on plant plankton. Without them, the plankton can reproduce more rapidly, which can lead to oxygen depletion and high nutrient levels in the lakes. Already, rising temperatures are promoting the growth of plant plankton in many places. “In lakes in the Pyrenees, where air temperatures are higher than in the Austrian Alps, these consequences can already be observed very clearly,” reports Sommaruga.

Fish removal made easy

Minnows are very small and therefore difficult to remove from a lake. In some cases, however, this very removal can actually preserve species in ecosystems. The FishME project investigated how quickly plankton and biological communities of invertebrates recover when the minnows are gone.

For this purpose, Sommaruga’s team removed fish from Lake Timmelsjoch, one of the few lakes in the Alps that is home to Daphnia longispina, a dark species of water flea. “Fish can easily see the fleas because of their coloration. That’s why they have already disappeared in many places,” explains the limnologist. This would also have happened in Lake Timmelsjoch if a colleague had not spotted trout in it in 2022. The researchers immediately obtained permission from the local agricultural community and set out nets. After a year, 13 fish had been caught and the impact on the ecosystem minimized. “With this we have shown that quick action can save costs,” says the limnologist. The operation took eight days – a minor effort compared to the large-scale removal measures that have to be taken once a stable fish population has become firmly established.

Lakes: resilient or vulnerable?

In order to minimize the negative impact of fish stocking on high mountain ecosystems, one first needs to understand these consequences and, secondly, be prepared to remove the fish. Currently, there is widespread ignorance. Of the people surveyed, 453 rejected fish removal, while 296 supported it. 596 people did neither – meaning they either have no opinion on the matter or are unaware of the consequences. In Austria, says Ruben Sommaruga, there is also a strong fishing lobby. So far, appeals have fallen on deaf ears with the Austrian Board for Fisheries and Water Protection and fishing associations. FishME now makes it easier to take action. The project has developed a toolbox with recommendations for fish removal, specifying, for instance, which and how many nets to use – tailored to the size and depth of the lake as well as the fish species and numbers.

High mountain lakes are finely tuned ecosystems. The more intact they are, the more resilient they are to negative effects such as global warming, but they are damaged by introducing fish into them – whether out of ignorance, as a source of income, or for sport fishing. “It is very important for people to understand that fish do not belong in high mountain lakes,” emphasizes Ruben Sommaruga. “Otherwise, the lakes could lose their function as the canary in the coal mine.”

About the researcher

Ruben Sommaruga is Professor of Limnology at the Department of Ecology at the University of Innsbruck. He studied biological oceanography in Montevideo, Uruguay, earned his doctorate in Innsbruck, conducted international research, and qualified as a professor in limnology in 1998. His research focuses on the ecology of aquatic systems, in particular (micro)planktonic ecology, biogeochemistry, photoecology, and the effects of global change on mountain lakes.

Publications

Early warning, rapid eradication of alien fish and ecological recovery in an alpine lake, in: Management of Biological Invasions 16 (in press)

Long-term changes of zooplankton in alpine lakes result from a combination of local and global threats, in: Biological Conservation 2025

Diet composition and quality of a Salmo trutta (L.) population stocked in a high mountain lake since the Middle Ages, in: Science of the Total Environment 2022

Minnow introductions in mountain lakes result in lower salmonid densities, in: Biological Invasions 2022