Polish history from the standpoint of "ordinary people"

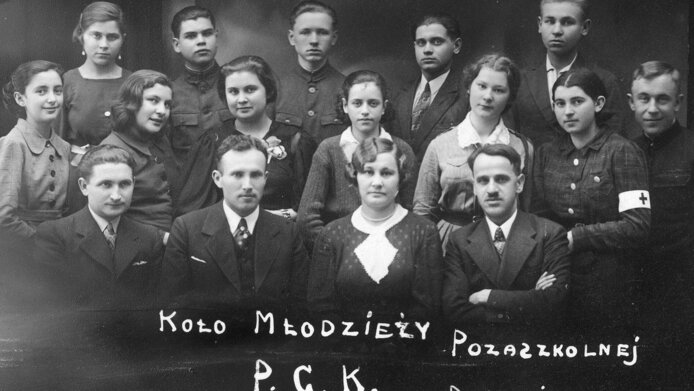

In the 1920s, Polish sociologists developed autobiography competitions as a way to preserve personal stories and biographical documents of workers, farming folk, young people and the unemployed. The best texts were awarded a prize. This “Polish method of social research”, as it was soon to become known internationally, exceeded all expectations that the researchers had nurtured. Until well into the 1930s, these competitions established a vibrant culture of autobiographical writing in a wide variety of social milieus from rural youth groups to Jewish cultural circles. What is more, published collections of these texts turned into bestsellers that were awarded literary prizes and thus also made the issue a subject of public debate. The roots of the method can be traced back to the co-operation between the Polish sociologist and philosopher Florian Znaniecki, who also taught in the USA, and his American colleague William I. Thomas from the University of Chicago. From 1918 to 1920, the two authors published the study The Polish Peasant in Europe and America, a classic in social research. In the 1930s, researchers from Columbia and Harvard also applied the “Polish method” to circles of National Socialist party members and Jewish refugees from Germany.

Evolution of social research

During the Second World War and thereafter, however, this humanistic model was replaced by a positivistic approach. It was only in the 1970s and ‘80s that the qualitative biographical method was rediscovered by the research community. “Yet without recalling that it had already been internationally established in the past”, explains Katherine Lebow. “It is interesting to note that the ‘Polish method’ is all but forgotten in both the German and English-language history of science”, observes the historian. Lebow now investigates why this is the case in the context of an Elise Richter Program funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Autobiographical writing as political participation

Apart from the contribution to the rise and fall of the trans-Atlantic history of social sciences, Katherine Lebow focuses on the public discourse which was sparked by the autobiography competitions and which firmly embedded them in the history of Eastern Europe. Based on original sources from Polish and US archives – including numerous unpublished texts – Lebow traces the intermeshing of science, literature and autobiography and its influence on the public sphere in interwar Poland. “It was unique. Not only the political elites or intellectuals had a say, but the common people as well. They gave themselves a voice through the writing competitions and raised awareness of exclusion and social injustice”, explains Lebow.

Instrumentalised memories

Whereas the interwar autobiographical texts focused on social and economic issues, eye-witness reports after the Second World War prompted a discourse about political ethics and human rights. But even during the War, the established culture of autobiographical writing lived on in Poland, albeit partly employing new strategies. In 1942, for instance, the Polish government in exile collected more than ten thousand files from deported Poles in order to document the Stalinist machinery, and Polish Jews systematically gathered eye-witness reports as of 1945. “This was an Eastern European and, specifically, Polish phenomenon”, notes Lebow. “But biographies were also harnessed in a countervailing direction”, adds the researcher. Writing competitions were initiated as well in order to serve communist propaganda purposes in Poland in the 1950s.

An important contribution to history

Although the texts submitted for the competitions were influenced by how questions were posed, the historian considers them to be important testimonies of intervention and political participation on the part of the population. “In addition, the reports reveal aspects that were not of interest to sociologists at the time, as for instance the fact that many women participated in the competitions or that languages other than Polish were used”, says Lebow.

Personal details Born in New York, Katherine Lebow, Ph.D., studied history at the universities of Yale and Columbia. From 2013 to 2014 she held a position of Research Fellow at the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI). Lebow is currently working on a monograph about “everyman” autobiographies in interwar Poland within the context of the Elise Richter Programme, a fellowship program in support of women researchers funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF. Her investigations are based on autobiographical texts, specialist literature and bodies of correspondence from 1918 until 1950, stemming from about a dozen archives in Poland and the USA. The most important collection has been preserved at the “Central Archives of Modern Records” in Warsaw.