Playing with brain data

If you watch children at play, you will notice that they are fully immersed in the world of their stuffed animals, building blocks or computer games, completely excluding the outside world. As adults, we also know this state of flow when playing or performing music, gardening or running. “Being engaged in play will take you to certain states of consciousness when engaging in the flow, and I wanted to know more about that. For me, neuroscience and neurointerfaces, specifically electroencephalography, were the way to go,” says Margarete Jahrmann of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, describing what triggered her research project “Neuromatic Game Art: Critical Play with Neurointerfaces,” which is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF. Electroencephalography (EEG) measures electrical activity in the brain and records this in the form of data streams and wave diagrams. Jahrmann was looking for artistic forms of representation through images and sound in order to make flow states and brain waves accessible in public performances and to educate people about neurointerfaces in a playful way.

A focus on brain waves

Jahrmann’s initial idea led to further research questions. Neurointerfaces are used not only for medical purposes, but you find them increasingly in consumer applications too, enabling, for example, also people free of medical conditions to control computers with their thoughts. From the consumers’ point of view, this opens up intriguing scenarios. While companies are marketing this technology as a playful approach to performing activities more efficiently, users of a brainwave measuring device do disclose a lot of their personal data, including not only personal details or usage data, but also emotions.

This inspired Margarete Jahrmann to tap the activist potential of art in order to question the limits of technologies. She put together an interdisciplinary trio of research fields, including neuroscience in the person of Stefan Glasauer, Chair of Computational Neurosciences at the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg (BTU Cottbus, formerly Klinikum München), digital philosophy with Mark Coeckelbergh from the University of Vienna, and Experimental Game Cultures at the Institute for Art and Society at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

Ludic research art

In order to combine basic research with art, Jahrmann relies on her core discipline, game systems. This is how she describes her rationale: “A game is a rule system that builds a model of the world that is subject to precise rules. This rule-based approach is comparable to scientific research, which lends itself well for a good collaboration between scientists and my arts-based research projects.” The “Ludic Method” she developed uses rule systems that are repeatable and quantifiable in an artistic context. “The special feature of my work is that all the game systems are shown publicly, which makes the experiments closer to reality than conducting them in the lab,” adds Jahrmann. The FWF-funded project “Neuromatic Game Art” has thus become a new form of experimental game art.

Public performances as a research venue

Jahrmann had planned many individual projects with live performances at different locations. The coronavirus lockdowns made that impossible at the start of the project, which is why the team launched the Neuromatic Brainwave Broadcast on Youtube involving likewise live viewers. While quite a challenge to do, these weekly broadcasts with EEG sets ultimately enriched the project, as the measured brainwaves were implemented with new visualization and sound each time.

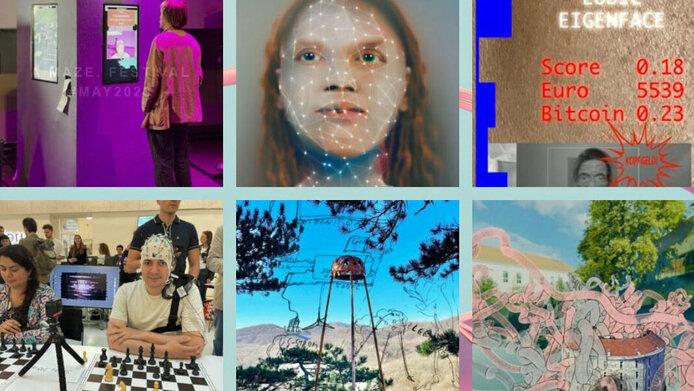

At a later point in time, there were events held at real locations. Jahrmann singles out two projects in particular: “Long before the hype about artificial intelligence (AI), in 2021, we did a neurophilosophical game chat. It involved an AI asking the technology philosopher Mark Coeckelbergh from our research team questions about the project,” explains Jahrmann. Another important performance was Zero Action in the Savings Bank which was about the feasibility of synchronizing signals from two EEGs in the banking hall of the Otto Wagner Postsparkasse, an architectural icon in Vienna. Jahrmann chose this setting very deliberately. “This poetic work entailed no money flows in the banking hall, but only the flow of thoughts.” The performance involved two female subjects who were shown lying down doing nothing, being in the flow, as it were. Their brain waves were measured via neurointerfaces and appeared live on a large screen, similar to stock market tickers. Observers were involved indirectly, since they influenced the subjects' thoughts simply by their presence.

Doing research and learning together

The project produced a variety of results for everyone involved. “The privacy aspect was important to us. In the Kopfgeld project, for example, we coupled EEG with facial recognition. When entering the installation, visitors very quickly and in rather unthinkingly agreed to the use of their biometric facial data. They only thought about it later on when we talked to them. Then they would ask, for instance, whether we could delete their data,” reports Jahrmann. The visitors experienced the opportunity to come into direct and playful contact with EEGs and sensors as a form of self-empowerment, since this setting had uncoupled the devices from their usual and somewhat scary medical environment.

The chosen research setting made apparent that the test subjects were also co-researchers, thus shifting the relationship with the research team and their respective roles. Jahrmann considers the central result of her project to be the realization that neurointerfaces such as EEGs have a central social significance and that they merit and necessitate further research using artistic means of expression: “We carry on from there with the new FWF-funded project 'The PsychoLudic Approach: Playing for the Future'. In his 'Rhetorics of Play' game theorist Brian Sutton-Smith explains why people play and why play is such an important cultural technique: because “everything we experience ourselves and opportunities to take action ourselves have a strong impact on us.”

Personal details

Margarete Jahrmann is an artist, researcher and founder of the Ludic Society. She completed her doctoral studies under Roy Ascott at the University of Plymouth, UK. Her methodological approach, the “Ludic Method,” was developed as part of her thesis. Jahrmann heads the Experimental Game Cultures unit at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna. Her PEEK project “Neuromatic Game Art” received approx. EUR 370,000 in funding from the Austrian Science Fund FWF. In 2023, she launched the follow-up PEEK project “The PsychoLudic Approach: Playing for the Future”.

Project website: https://neuromatic.uni-ak.ac.at

Exhibitions

2022: Narrenturm Mindgame: Mindworm Blaster Augmented reality piece. Part of the permanent exhibition of the [Artificial Museum] (Jahrmann, Glasauer, Luif, Wagensommerer)

2022: Nubes Mental. Objeto de Juego. (Jahrmann, Glasauer, Wagensommerer, Kedl) participation in the 14th Havanna Biennale

2021: SPIKE_Clouds_Climate.Mind. A play concert performance for non-human actors and various minds. Performance (Jahrmann, Glasauer, Wagensommerer) in the context of the Hybrid Play #RealityCheck Festival. Festspielhaus Hellerau Dresden

Publications

Dobrosovestnova A., Coeckelbergh A., Jahrmann M.: Critical Art with Brain-Computer Interfaces: Philosophical Reflections from Neuromatic Game Art Project, in: C. Stephanidis et al. (ed.), HCI International 2021 – Late Breaking Papers Cognition, Inclusion, Learning, and Culture, Springer Nature 2021

Jahrmann M.: Ludic Meanders through Defictionalization: The Narrative Mechanics of Art. Games in the Public Spaces of Politics, in: Suter, Beat, Bauer, René and Mela Kocher (Hg.), Narrative Mechanics. Strategies and Meanings in Games and Real Life, 257–278, Bielefeld: transcript 2021

Jahrmann M.: Neurointerfaces as means of Artistic Research or Expanded Game Art, in: Abend P., Beil B., Ossa V. (eds.), Playful Participatory Practices. Theoretical and Methodological Reflections, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 131–147, 2020 Preprint