Opera and politics

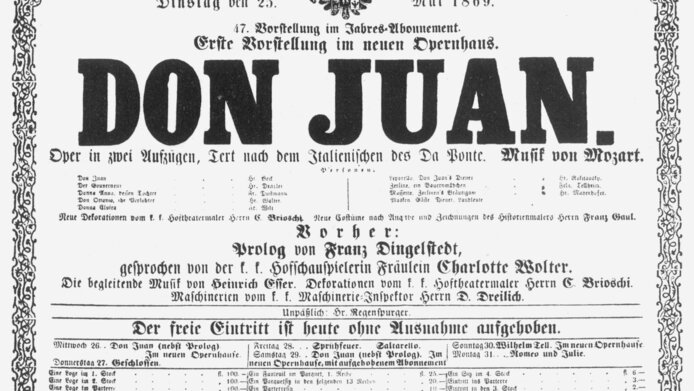

“It is interesting to note”, says Christian Glanz, “that in 19th- century Austria opera was not used as a vehicle of political communication in Vienna.” At a time when Verdi in Italy and Wagner in Germany were conjuring up powerful sonic visions, Vienna experienced a strange creative lull. The Court Opera, as it was called then, was alive but content merely to tap the repertoire of Mozart, Gluck and the Italian composers. And the Emperor only loved the Radetzky March in any case. “A political history of opera in Vienna between 1869 and 1955” is the title of the FWF-funded project under the lead of principal investigator Christian Glanz from the Department of Musicology and Performance Studies at the University of Music and the Performing Arts, Vienna. “1869 is one of the last years that saw the liberals as the dominant political force in Vienna. Three years earlier Austria had left the German Confederation, two years earlier it had adopted the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, and four years later came the stock exchange crash and the cholera epidemic”, is how Glanz describes the situation at the time. Above all, it was in 1869 that the Court Opera opened its doors.

Interactions

“It was our tenet”, notes Glanz, “that the institution reflects social and political events and developments.” The opera as a seismograph, as it were. “But we have to state quite clearly that there is no push-and-pull situation in this context”, adds Glanz. Not every political event had an immediate impact on the Vienna Opera. Much more frequently one finds changes in mindset, developments heralding the advent of political events. Changes in opera lyrics in order to permit a work to be performed, for instance, or attempts at exerting influence from behind the scenes. The most striking example was the illegal Nazi organisation cell group set up at the opera in the 1930s.

The project subdivided the opera’s history into five phases: the Ringstraße culture of the 1870s, the year 1897, the opera during the First Republic, the period of dictatorship, denazification and reconstruction. – Carefully selected examples illustrate the interaction between life in Austria and performances at the opera. “Originally, the second phase was supposed to cover the period between 1892, the year of the International Exhibition of Music and Theatre, and the year 1907, when universal male suffrage was introduced”, explains Glanz. A time that was densely packed with events. So densely packed, in fact, that this phase ultimately focuses on one single performance and a single year: 1897.

Pivotal year of 1897

A great deal is happening in 1897: Karl Lueger is elected mayor of Vienna again, and along with him arrive mass political parties and pure populism; “old Vienna” is pitched against “new Vienna”; the indigenous local culture of the city is promoted as the antithesis to elitist high culture; the Minister-President of Cisleithania, Kasimir Felix Badeni, submits his language ordinances for Bohemia and Moravia to the Imperial Council, which provokes street fighting and a state crisis, and – Gustav Mahler is appointed director of the Court Opera. Mahler decides to put Friedrich Smetana’s Dalibor on the programme on 4 October 1897, the Emperor’s name day, as the first premiere under his direction. Dalibor features a protagonist who revolts against king, nobility and Poland and supports the peasants. While successful in artistic terms and reviewed favourably by the critics, it created a political stir spurred on by certain media, such as the Deutsche Volksblatt, the Deutsche Zeitung and the Reichswehr, the latter considering the performance as representing a “subjugation of the Court Opera”. Project team member Tamara Ehs concentrated on the “pivotal year of 1897”, and she notes: “If it [Dalibor] was indeed a political act, Mahler abandoned this position shortly afterwards; at the beginning of the season he had announced a performance of Smetana’s Libuse but did not follow through because of the polemical debate and attacks that occurred.”

The First Republic

The institution is the Court Opera, after all, and even under Mahler’s direction the emphasis lies on “court”. Financed by money from the private coffers of the Emperor, the opera is more of a decoration than a place of artistic commentary on contemporary events. Such commentary shifts to other art spheres. During the First Republic, however, this imperial jewel is awarded a new task. Under its new name of State Opera and backed by an all-party consensus, it is designed to tell the world about Vienna’s and Austria’s supremacy in all things musical. Minor political hiccups such as those accompanying the ballet Schlagobers and the opera Jonny spielt auf did nothing to diminish that mission. The opera even extended its outreach by entering into a partnership with the Salzburg Festival, thus enabling successive federal governments until the period of Austrofascist dictatorship to harness Salzburg for national purposes. “It is also interesting to note the position the opera occupied after 1945”, relates Glanz. “Official voices equated the reconstruction of the opera house with the post-war reconstruction of Austria as a whole. They raised funds for this reconstruction in the USA, arguing that it helped distance Austria from Germany.” – The Opera as an ornament charged with symbolic significance. The results of the project will be used for a book inter alia on the Vienna State Opera’s 150th anniversary in 2019, thus providing a link between the history of the institution and the political and social history surrounding it.

Personal details Christian Glanz is an associate professor at the Department of Musicology and Performance Studies at the University of Music and the Performing Arts, Vienna. Between 2012 and 2016 he directed the project “A political history of the Vienna Opera between 1869 and 1955”.

Project website: http://www.mdw.ac.at/imi/operapolitics Publications and contributions