On secret mission in post-war Austria

The Cold War is over, or is it? The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine brought with it a woeful revival of this division of the world that was believed to be over, of these supposedly outdated ideologies, value systems and stereotyped antagonisms. Given that intelligence services play a major role in any war, research on Czechoslovak intelligence services post-1945 also relates to the here and now. The players in post-war Austria, their operations and networks are currently under investigation in an FWF-funded project at Graz University. “Once more, we see that there is interaction between 'big history' and the micro level. For the recruitment of spies, the precarious economic situation of many people during the Cold War may well have played a greater role than ideology,” explains historian Barbara Stelzl-Marx.

Stelzl-Marx and her multilingual team are pursuing a comparative approach using international sources and archived material. Dieter Bacher, Phillip Lesiak, Sabine Nachbauer and Martin Sauerbrey are building a database that documents the course of events. For this purpose they are networking with the international research community. “One of the spy recruits was an Austrian businessman from Vienna, about whom we found an investigation file by the US Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC). We were able to extract his surname and his network from the Czech archives, and we found further information in London, and in Austria there is a file from an official investigation relating to his partner,” notes principal investigator Stelzl-Marx by way of example. Hence, the Allied Forces had to establish not only administrative and military structures in Austria, but also secret-service structures in order to guarantee strategies and security.

The historian Barbara Stelzl-Marx heads the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Research on the Consequences of War in Graz. She conducts research among other topics on the consequences of the Second World War and the Cold War.

More information

Information gleaned by people

As the term ‘secret service’ suggests, information of this kind is not just found lying around. It was vital for the project to have access to two Czech archives: the bezpechostnich slozek archive (ABS) in Brno and the ministerstva zahraničních věcí archive (AMZV) in Prague. Other valuable sources for the researchers were the files of the American CIC and the British secret service (the divisions Field Security Sections and the “Intelligence Organisation Austria”), files of the Austrian Interior and Foreign Ministries, as well as individual Soviet data sets found at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Research on the Consequences of War, the national research partner in the project.

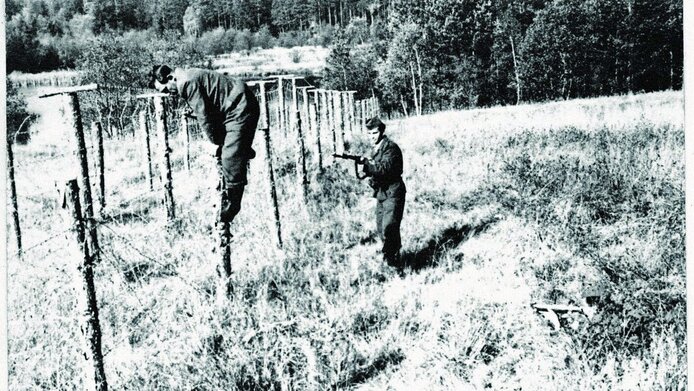

In most cases, work for the secret service was not as adventurous as it appears in James Bond movies and not as ideology-driven as in classic espionage literature. “HUMINT”, short for human intelligence, rarely involved guns and raincoats with upturned collars. Sometimes it was just about finding out one piece of the puzzle, such as which trains ran from Austria to the Soviet Union via Hungary: “Many absolutely ordinary people, of whom we are totally unaware today, cooperated with the Czechoslovak services, collecting and passing on information. In Austria, these included many displaced persons in camps in the Soviet occupation zone or stateless individuals in particularly dire circumstances. Later on, they also included dissidents,” notes Stelzl-Marx. Public figures who also worked for the secret service, such as the former mayor of Vienna and ORF journalist Helmut Zilk (code name Holec), were the exception.

Trapping mice

In order to learn the reasons why people had contact with secret services, the research team uses the MICE model. M stands for money, i.e. a substantial topping up of a meagre or unsteady income for many. I stands for ideology, C for coercion, and E for ego or excitement, since for some informers this involved an ego boost, a sense of being special and doing something exciting. Espionage involved not only (monetary) benefits, but also risks. Between 1948 and the 1960s, the operations of two services, the Sbor národní bezpečnosti (SNB) and the Státní bezpečnost (StB), continuously strengthened the axis with the Soviet Union. The predecessor state of the Czechoslovak Republic (CŠR) was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and freed by the Red Army in 1945. A government in exile was formed in London in 1940. At the behest of Moscow, President Edvard Beneš formed a coalition government of the “National Front”. Two military and two civilian intelligence services prepared the takeover by the Communist Party. With the February revolution in 1948, the country came under communist rule, where it remained until the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

Austria as a hub for secret services

The present research once again confirms that Vienna was (and still is) a hub for secret service operations. The answer to the second major question as to whether the Czechoslovak secret services were particularly active in Austria is also answered in the affirmative by Stelzl-Marx. “Austria was an important operational area, thanks to its location directly bordering the Iron Curtain and also to the fact that it was under the administration of the Allied Powers (USA, France, Soviet Union and UK) until 1955. Vienna, an operations area for all four Allies, and the city of Salzburg, which was in the US zone, were hubs for activities by various secret services.” Linz mainly saw technological and industrial espionage and not so much activities directed against national politics or the economy. The mission was rather to gain information about neighboring western countries and other foreign services. As in the Cold War, France was not involved.

Set to run until August 2024, the project has already resulted in important collaborations, such as an agreement with the archive in Budapest (ABTL) and the organization of the international “Need to Know Conference” in Graz in 2023.

Personal details

Barbara Stelzl-Marx conducts research on the consequences of the Second World War and the Cold War, children of war, forced migration, remembrance and commemoration. Elected “Scientist of the Year” 2019, she heads the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Research on the Consequences of War, Graz - Vienna – Raabs. Stelzl-Marx holds a position as a contemporary historian at the University of Graz and she is a member of the Research, Science, Innovation and Technology Development Council.

After studying history, English and Slavic studies in Graz, Oxford, Volgograd and at Stanford University, as well as under an FWF Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship in Moscow, she was an APART Fellow of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and received several prizes and awards for her work.

Publications

Dieter Bacher: Rudolf Vala: Czechoslovakian Intelligence in Austria 1949–1951, in: International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 2023

Magdolna Barath, Dieter Bacher (eds.): A Frontline of Espionage. Studies on Hungarian Cold War Intelligence in Austria, Budapest – Pecs 2021