No peace without rapprochement

The life of the native Swiss and later Habsburg envoy Johann Rudolf Schmid zum Schwarzenhorn (1590-1667) took an abrupt turn while he was still a young man: in the early 17th century he became a prisoner of war of the Ottoman empire and suffered long years of captivity. Thanks to his language skills he was able to elevate his social status from mere slave to interpreter. In this capacity he made contact with Habsburg envoys, who successfully worked towards his release in 1624 and facilitated his entry into the diplomatic service. At a time when diplomatic careers were based on family background and wealth, Schmid’s beginnings were unusual. They were also unusual because his success was based on intercultural skills and his proficiency in the Ottoman language.

“At that time, it was rare to have envoys going to Constantinople who had a command of the local language. Most of them had to use interpreters, so-called ‘dragomans’. Schmid, however, had personal contacts with the Ottomans and learned many things at first hand. This is what makes his reports so intriguing,” explains the historian Arno Strohmeyer of the University of Salzburg.

Communication creates knowledge

Schmid was sent to Constantinople several times as a Habsburg envoy. In 1649, a diplomatic mission of several months was particularly important for maintaining the peace between the two empires. The manner in which Schmid and his assistant Johann Georg Metzger recorded the events in Schmid’s travel report is at the centre of a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF. The historian Strohmeyer and his team of researchers from the University of Salzburg, the University of Graz and the Hungarian University of Szeged analyse various aspects of the diplomatic missives. The communications include letters sent between Schmid and the Imperial Court in Vienna, instructions from Emperor Ferdinand III, the “Secret Report”, the final report (Finalrelation) and travel reports. This is the first time that researchers are investigating the mission of 1649 in terms of media interfaces, examining, for instance, where text passages were copied from one medium to another.

The analysis also provides new insights as to how knowledge about the Ottomans was gained in Central Europe and the impact intercultural rapprochement had in this process. “You have to bear in mind that, for a long time, these correspondences were the central form of communication between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans. A significant portion of the knowledge about the Ottomans was gathered in the context of diplomatic missions, which means that written correspondence is the most important historical source of information,” Strohmeyer notes. Thanks to his language skills, Schmid was also very familiar with the Ottoman culture, which is why the researchers’ analyses illustrate phenomena such as adapting to the foreign culture (acculturation) or adopting aspects of a foreign culture (assimilation).

Everything was important

The documentation is plentiful, since Schmid sent a letter to the Habsburg Emperor every two to three weeks. Preserved in its entirety, this valuable correspondence is kept in the Austrian State Archives in Vienna. There were always several copies made of each letter and these were sent to Vienna by different routes. In addition, sensitive passages were encrypted. The researchers were surprised by the very diverse content, ranging from political events to the seating arrangements at festivities or the weather, which provided a very detailed impression of everyday life. The envoys had the remit to report on everything they deemed important, but were expected to do so from a neutral and “objective” point of view wherever possible. These expectations had an impact on how events were reported.

The analysis has revealed examples where Schmid underlined his own successes and sober attitude, while for instance portraying a high-ranking Ottoman as highly emotional. Schmid reinforced this rational-versus-emotional portrayal even more by including verbatim quotes. He could do this credibly, because he spoke the language. While the letters and reports illustrate the diverse everyday activities of the envoy, the travel reports – to the extent that they are still preserved – furnish more context.

A single travel report was rediscovered

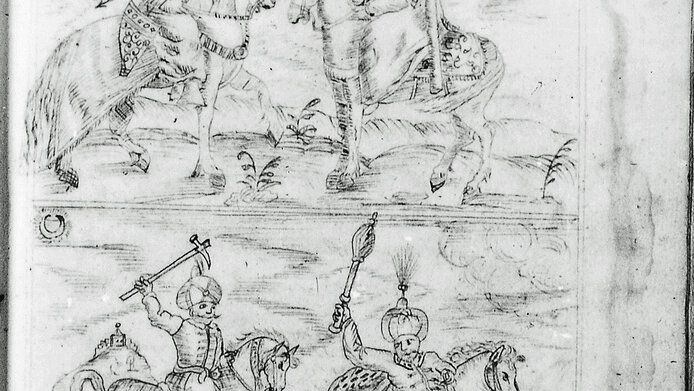

Thanks to the commitment of the historian and project team member Anna Huemer, an original travel report by Johann Georg Metzger that had been believed lost was rediscovered after a laborious search at Stiebar Castle in Lower Austria. “That was a really lovely moment when we finally discovered it in a cabinet on our second visit to the castle archives,” Strohmeyer recalls. After all, only this one travel report exists of the diplomatic mission in 1649. The document also derives its great value from the fact that it provides a different perspective on the events mentioned in letters and reports. Detailing the timeline of the mission, Metzger also adds historical information, for instance on city history, and provides numerous illustrations of the country and its inhabitants.

With the help of computer-assisted text analysis, the team is now able to demonstrate the strong links between the different. Developed by Vienna-based computer scientists, the tool used to analyse intertextuality reveals who composed which passages or which texts were added – at the time, passages taken over from other texts were not marked as quotes. “With such a great quantity of texts, it would otherwise be difficult to identify crosslinks. When looking at the description of the first visit to Sultan Mehmed IV, we now know which passages were copied from letters in the travel report,” Strohmeyer explains.

Dismantling barriers step by step

In terms of knowledge transfer, Schmid’s letters and reports communicated two things: on the one hand, they reinforced existing knowledge about the Ottomans, as well as stereotypes and hostile prejudice. On the other hand, they also dismantled some of them, for instance by differentiating between the people he met. As an example, Strohmeyer mentions the stereotype of the Ottoman ruler as a tyrant directing a violent regime. “While Schmid persists in using the term tyrant in his final report, he describes the regime as a blend of monarchy, aristocracy, democracy and triumvirate. In this way, he draws a differentiated picture and abandons the stereotypes of tyranny.”

Schmid illustrates that the practice of interculturality, i.e. taking an interest in others, speaking other languages, personal contacts and first-hand experience, makes an essential contribution to uprooting simplistic perceptions of good vs. evil and overcoming mental barriers. Mutual rapprochement and an emphasis on equality and friendship in word and deed filled the peace treaties with life – a lesson as significant today as it was then.

Arno Strohmeyer is Professor of Modern History at the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg and Director of the Institute for Habsburg and Balkan Studies (ihb) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His main research interests include interculturality, peacekeeping and diplomatic history. In the context of the research project “The Mediality of Diplomatic Communication” (2017–2021), which is funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF with roughly EUR 360,000, Georg Vogeler of the University of Graz and Arno Strohmeyer together with his team are also developing a “digital edition”.

Publications

Anna Huemer: Von knobloch und zwieffel zu den bulgarischen weibspersohnen. Balkanbilder im Spiegel der Reiseberichte von Hans Ludwig von Kuefstein und Johann Georg Metzger (1629/1650), in: Endreva, M. u. a. (Hg.): Der Donauraum als Zivilisationsbrücke. Österreich und der Balkan. Perspektiven aus der Literatur- und Geschichtswissenschaft, Königshausen & Neumann 2020

Christoph Würflinger: Die Verschlüsselung der Korrespondenz des kaiserlichen Residenten in Konstantinopel, Alexander von Greiffenklau zu Vollrads (1643–1648), in: Chronica – Annual of the Institute of History, University of Szeged, 6–23, 2020 (PDF)

Arno Strohmeyer: Der Dreißigjährige Krieg in der Korrespondenz des kaiserlichen Residenten in Konstantinopel Johann Rudolf Schmid zum Schwarzenhorn (1629–1643), in: Rohrschneider, M., Tischer, A. (Hg.): Dynamik durch Gewalt? Der Dreißigjährige Krieg (1618–1648) als Faktor der Wandlungsprozesse des 17. Jahrhunderts, Münster 2018 (PDF)