How intestinal bacteria can cause depression

It has been known for quite some time that the proverbial “gut feeling” has a real medical basis. The intestine has its own nervous system, also known as the “abdominal brain” owing to its size and complexity, and it is closely connected to the brain. Processes in the intestine cause changes in the brain and, conversely, psychological factors influence the intestine. How far this interaction goes and how exactly it works, however, has not yet been fully understood. There are indications that the intestine may be involved in the development of psychiatric diseases. A research group headed by the neuropharmacologist and neurogastroenterologist Peter Holzer from Graz was able to identify a number of concrete factors that can trigger psychological changes in mice in a recently completed basic-research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF.

Intestine affects the brain

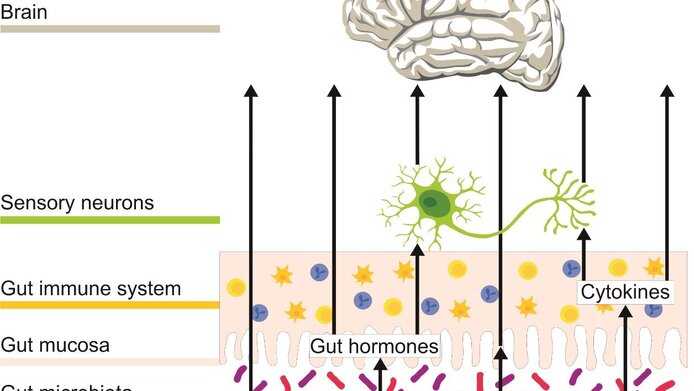

“The connection between the intestinal nervous system and the brain has been known for a long time, but the situation has become more complex if you consider the most recently published studies,” says principal investigator Peter Holzer. “In addition to the direct neural pathways between intestine and brain, which we have known about for a long time, there are many intestinal hormones that carry messages to the brain, as well as a huge immune system that releases messenger substances when stimulated. In recent years, the gut microbiota has become an additional factor. This consists of a huge number of monocellular organisms that also release substances and are believed to play an important role in the body’s information system.” According to Holzer, many people are familiar with a strong connection between brain and gut. “But we are not usually aware of such an amount of information reaching the brain from the gut. This information is fed into brain areas that are important for our mood and emotions.”

Feeling ill because of bacteria in the intestine

Holzer and his team have spent five years investigating various signalling pathways which intestinal processes can use to influence the brain. One objective of the project was to clarify how certain bacteria in the gut alert the immune system and thus trigger a feeling of illness. “The immune system learns early on to tolerate the microorganisms in the gut. That starts in infancy,” explains Holzer. “When some substances produced by bacteria penetrate the intestinal wall, this certainly creates an immune reaction and, associated with it, a sense of being ill.” Specifically, he investigated the so-called “endotoxin lipopolysaccharide” (LPS), which is released by certain intestinal bacteria and stimulates the immune system, giving us a sense of being ill. “If you suffer an infection with bacteria you will feel tired, have muscle pain, lose your appetite and become withdrawn. This is a sensible reaction of the body, helping it to cope quickly with the infection,” says the researcher. “There is evidence, however, that this reaction could be triggered in humans by intestinal bacteria, even when there is no infection at all.” Holzer’s team were able to show that other substances produced by bacteria, so-called “peptidoglycans”, enhance the effect of LPS. “We believe that lipopolysaccharide is only one of several factors contributing to the development of mental illness.”

High-fat diet as a risk factor for depression

Holzer sees this physical reaction of “feeling ill” in the larger context of intestinal influences on the human psyche, and in particular as a possible trigger for psychiatric diseases. “We know from psychiatry and nutritional science that being overweight increases the risk of depression and depressive mood disorders. Moreover, it has also been known for about 15 years that there is a great difference between the gut microbiota of healthy and severely overweight people,” Holzer notes. One result of the project provides concrete information on how processes in the intestine can trigger depressive behaviour. The team subjected mice to a high-fat diet and analysed their behaviour. In addition to the chemical changes in the brain that are associated with depression, they also detected concomitant behavioural changes. According to Holzer, it is difficult but not impossible to detect this in mice. “Depressive people lose their joy in certain things. This anhedonic, or listless, behaviour was something we were able to identify in the mice that were given a high-fat diet.” Their method was to offer the mice regular water and sugar water as an alternative. Whereas healthy mice prefer sugar water, the mice in Holzer’s experimental setup went for it much less often. In the next step, their gut microbiota was severely depleted by the administration of antibiotics to find out whether intestinal microbes contributed to depressive behaviour after a high-fat diet. The results are due to be published soon.

Fat hormone as a trigger

Holzer’s team has also identified a possible signalling pathway to explain how depressive behaviour can be triggered by a high-fat diet. The hormone “leptin”, which is released by fat cells, seems to play a role here. Mice that are unable to produce this hormone gain the same amount of weight as other mice when they eat high-fat foods, but tend not to show the behaviour associated with depression. “The role of leptin has not yet been clearly settled in the literature. We were able to show at least that leptin is important in this context.” Holzer suspects that the release of leptin is linked to short-chain fatty acids produced by microorganisms in the intestine from fibre-rich food. The microbiota of the intestine therefore also seems to play an important role in the context of depression induced by obesity.

Personal details

Peter Holzer is Professor of Experimental Neurogastroenterology at the Medical University of Graz and Head of the Research Unit for Translational Neurogastroenterology. For three decades his research has focussed on the communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain.

Publications

Hassan AM, Mancano G, Kashofer K, Fröhlich EE, Matak A, Mayerhofer R, Reichmann F, Olivares M, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Claus SP, Holzer P.: High-fat diet induces depression-like behaviour in mice associated with changes in microbiome, neuropeptide Y, and brain metabolome, in: Nutritional Neuroscience 2018

Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, Reichmann F, Jačan A, Wagner B, Zinser E, Bordag N, Magnes C, Fröhlich E, Kashofer K, Gorkiewicz G, Holzer P.: Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication, in: Brain, Behaviour and Immunity 56, 2016

Farzi A, Reichmann F, Meinitzer A, Mayerhofer R, Jain P, Hassan AM, Fröhlich EE, Wagner K, Painsipp E, Rinner B, Holzer P.: Synergistic effects of NOD1 or NOD2 and TLR4 activation on mouse sickness behavior in relation to immune and brain activity markers, in: Brain, Behaviour and Immunity 44, 2015