From anxiety to action

It is an interesting phenomenon: climate change is becoming more and more visible, the threat is growing – a situation that seems to call for action. Actually, most people respond with evasion where large and existential threats are concerned. “People tend to avoid the threat and respond indirectly”, notes the psychologist Eva Jonas. Instead of changing their lifestyle and confronting the situation, many people respond by getting angry towards other communities. But what point is there in denigrating another culture for solving climate change? – None whatsoever, since the problem is not solved by suppressing or “outsourcing” it, which only delays the impact. “This ethnocentric attitude doesn't develop immediately when people are threatened but after a delay. It will emerge at some later point and lead to these defensive and denigrating reactions”, explains Jonas who conducts her research at the University of Salzburg.

Ways of overcoming anxiety paralysis

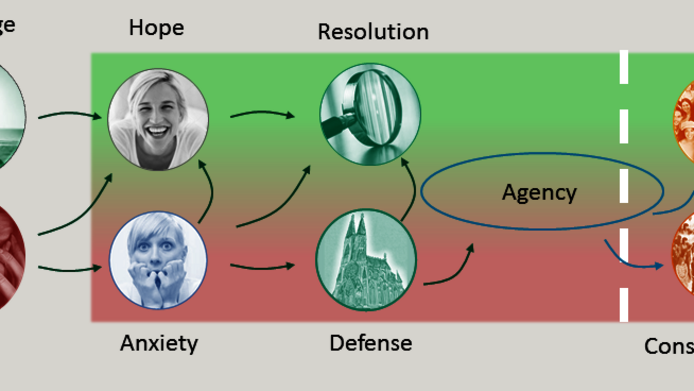

For many years, Eva Jonas has been studying issues related to collective identity, loss of control and anxiety and the underlying psychological processes. She combines methods from social psychology with neuro-psychological examinations in order to track physical reactions of individuals alongside external observations of them. The current study on climate change is one of several designed to supply Jonas and her team with additional building blocks on what worldwide research calls “experimental existential psychology”, a branch that developed out of the terror management theory. One of the unsolved questions in this context relates to the exact nature of the process between threat and defence. Funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, the project From Anxiety to Approach aims to supply answers. When human beings feel existentially threatened their body reacts with an “inhibition response” which, among other things, leads to the above-mentioned avoidance behaviour. At first the body remains in a state of irritation and anxiety and needs re-orientation. “Approving your own culture and denigrating another may bring this necessary cognitive clarity and orientation”, explains Jonas. This re-orientation is necessary to transition to an active state. Hence, the inhibition phase explains why people who are threatened defend themselves by denigrating others or distancing themselves from others – they do it in order to get out of the anxiety paralysis and act. The result of that action will then depend strongly on the context in which someone lives – for instance the values of the group they feel affiliated to, the dominant culture in general or individual role models.

Social motivation as a process model

Yet, as the psychologist from the University of Salzburg emphasises, one cannot claim that people generally indulge in denigrating or more conservative behaviour after a threat. In their investigations, the researchers observed that people also had a wish for change after experiencing a loss of control. “It always depends on what the situation requires and what is considered to be good behaviour”, says Jonas and goes on to underline: “In times of crisis and terror threats, people orient themselves more strongly along prevailing norms. As a society we therefore have to be careful as to which values are dominant in public debate.” So as not to remain in anxious paralysis in the transition between threat and defence, a key element is the capability to act, as Eva Jones illustrates by means of a process model her team developed in the ongoing FWF project. The researchers want to find out what the prerequisites are for a constructive response to threats and what might be the impact of a targeted motivation to act. “First of all we need to accept that people defend the core elements of their culture in order not to lose orientation. But there is a margin of manoeuvre within which one can define that culture. For instance, whether the focus is to be more on exclusion or integration.” The psychologist explains that it is particularly important to acknowledge someone’s anxiety and be sensitive when people get fearful and stuck in “inhibition mode”.

Security as a prerequisite for the ability to act

Angela Merkel’s culture of “we can manage this”, for example, went in this direction when the German Chancellor pronounced an anxiety-inducing situation (the influx of refugees) as a challenge. But that in itself was not enough. “Some shared her optimism, others sank into anxiety and then paralysis and, finally, resistance”, runs the analysis of Jonas. “This is why one has to find something that gives people first of all a sense of security so as to pull them back into optimism and then offer them creative leeway. In this process one needs safety nets”, stresses the psychologist. “Then you can achieve an ability to act via a constructive path.”

Personal details Eva Jonas heads the Section of Social Psychology at the University of Salzburg. The scholar is a seminal figure in the German-speaking area in the field of terror management research which deals with human awareness of one’s own mortality. Her research focus lies on social cognition and motivation under the influence of threats such as loss of control, injustice and existential anxiety.

Publications