Smartphones: treasure troves of raw materials

Smartphones, washing machines, power tools: all of these smart gadgets contain materials such as gold, copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium. Frequently, these raw materials are mined in conflict zones and assembled to electric circuits under conditions that are harmful to the workers’ health, only to end up on contaminated landfills after a short period of use. And as the world seeks to increase the share of renewable energy by increasing the number of wind turbines, solar plants and electric vehicles, the demand for these materials is expected to further soar in the years to come. The EU Commission has predicted an 18-fold rise in the demand for lithium alone for 2030.

Congo – a poor country rich in raw materials

The dynamics of the fierce competition governing the raw materials market can be best observed in Congo, which, despite its exceptional raw materials reserves, ranks among the world’s poorest countries. As much as two thirds of the cobalt traded worldwide for use in the batteries of laptops, smartphones and cars are mined in the Central African country. The people who live there, however, mostly do not benefit from the profits gained this way. The lion’s share is produced by international mining companies, but there are also about 200,000 people working in what is called informal small-scale mining: among them children and teenagers. Their working conditions can only be described as inhumane. They dig narrow, unsecured shafts into the mountain to manually scrape off the ore using pickaxes. Every now and then shafts collapse and bury people beneath them, causing them to slowly and painfully suffocate. The waste water pollutes rivers and groundwater.

Profits are made elsewhere

The rocks containing cobalt are sold on local raw materials markets – mainly to Chinese intermediaries. The prices paid hardly cover life’s bare minimum, and very often a share must be handed over to corrupt officials as protection money. Wholesalers then ship the cobalt to China, where it is processed and put to use in batteries. “Africa, South America, Indonesia or northern Sweden – in none of these places do the locals benefit from the mines,” Stefanie Wuschitz drives home the crux of the matter.

A race for the “white gold”

When the Australian mining company AVZ Minerals discovered what is thought to be the world’s largest lithium reserve in test drills in the southeast of Congo in 2019, international companies started scrambling to unearth the treasure. The prices paid for the “white gold” on the world market had already exploded in the years before as electric mobility took off. In 2021, as much as 100,000 tons of lithium were produced around the world. And the demand is expected to reach two to three million tons per year by 2030. China is the biggest player in the lithium business. The Chinese company CATL is the global market leader when it comes to batteries for electric vehicles. The government in Beijing, in turn, is trying to control access to lithium by buying shares in joint ventures.

Fertile zone between the fields

Stefanie Wuschitz, a media artist at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, has for years looked into ways of producing electronic devices using recycled and organic materials. Her work is rooted in science as much as in art and technology. An extremely fertile zone for innovative ideas, as she points out.

Raw materials export trumps democracy

The scientist became interested in this topic through her involvement in a research project dealing with the history of Indonesia and its gold and copper mines – “a textbook example of a country with formerly democratic and just social structures that was thrown into a dictatorship for the gains of raw materials export,” she recounts. She is referring to a scheme called the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), a mechanism that enables multinational companies to sue governments if they can assert that domestic laws are lowering their investments’ value. It is a way for corporations to bypass national legislation.

The problems of a society where everything is disposable

For Wuschitz, the core of the problem is our society’s paradigm of single use. “Maintaining and caring suffer from a bad rep in our society. That’s the case for childcare as much as for caring for the old – the regard for care work is as low as its pay. And the same goes for machines,” she says. What she proposes instead is a circulatory economy, in which things are not only maintained and repaired but where future recycling is already considered during the design and production process.

Urgently needed: more appreciation for care work

A growing number of innovative companies seem to have realized this. “We are artists and work with utopias, but there are also many companies out there where people have understood that profit can be made not only from selling a product but also from maintaining it in the long run,” she explains. For this scenario to take root, it will take more appreciation and better remuneration for the care work delivered in our society.

E-waste as a huge source of raw materials

It is still a tedious and expensive process to source valuable materials from e-waste, which is why the recycling quota continues to remain as low as it is. But there is no doubt that e-waste is a huge raw materials source that has yet to be tapped. The amount of discarded electronic devices is mindboggling and according to United Nations estimates, it is increasing by more than 50 million tons every year. The waste contains metals such as gold, silver, cobalt and copper – in concentrations not found in any other reserve. E-waste is currently the world’s fastest growing waste stream. This is due to our lifestyle that entails an ever-growing number of electronic devices which are used for shorter and shorter periods of time. Fixing machines that are broken used to be the norm. Today, spare parts are hard to get, the costs for repairing something often exceed the price of a new model, and some machines simply cannot be disassembled. Experts have pointed to the urgent need to reverse this trend for years, for instance by introducing minimum standards and information duties for manufacturers on the projected lifespan and repairability of their products.

Exporting garbage to Africa

Today, our waste problem often ends up in Africa. Ghana’s capital Accra is home to one of the world’s largest e-waste landfills. Every year, Europe ships about 250,000 tons of discarded electronic appliances to Accra, where they are burned to produce usable metals. The little money people make this way is paid for with their health. Toxins can be found in the air, the soil and the water. The Basel Convention forbids exports of such hazardous waste from the EU, which is why the electronic scrap is labelled as “second-hand”.

EU directive on manufacturers’ responsibility

The EU has made efforts to support the development of a circulatory economy through legislation such as the Waste of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive and calling upon politicians around the world to implement an extended version of manufacturers’ responsibility, which would legally oblige manufacturers to take back, transport, dispose of or recycle products that they have sold. “You have to consider every step in the entire product life cycle, from design to collection to suitable treatment of the waste generated,” Wuschitz says.

Electronics from recyclable materials

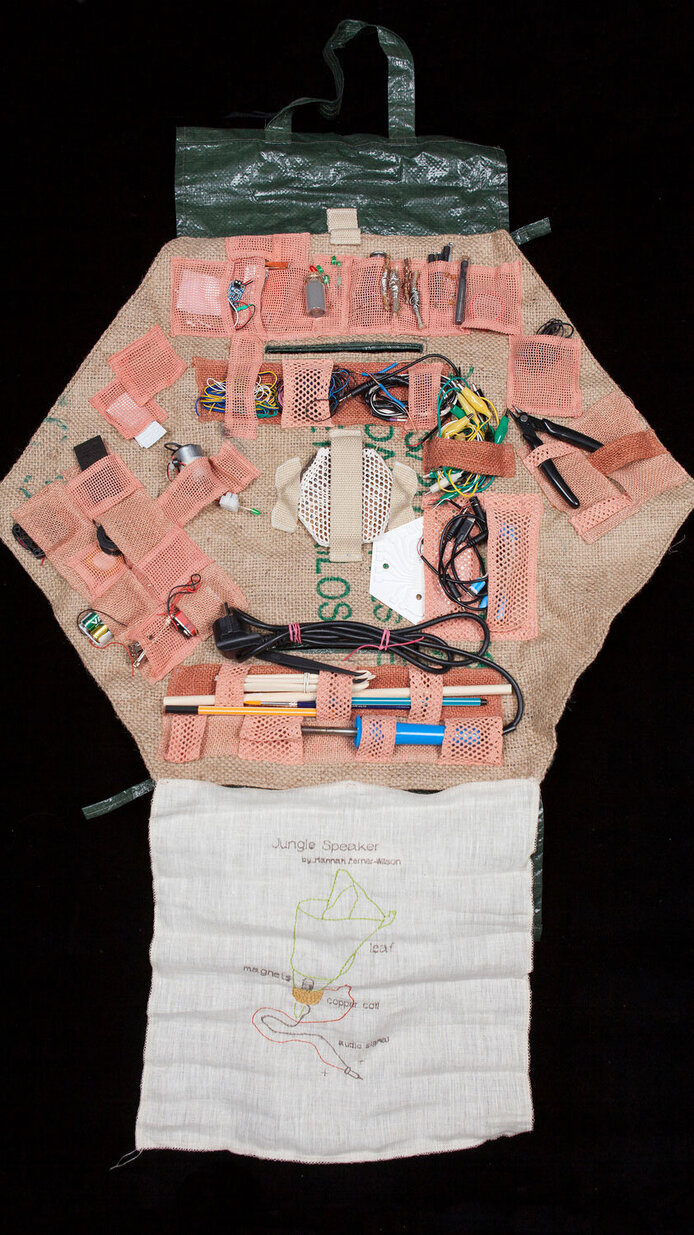

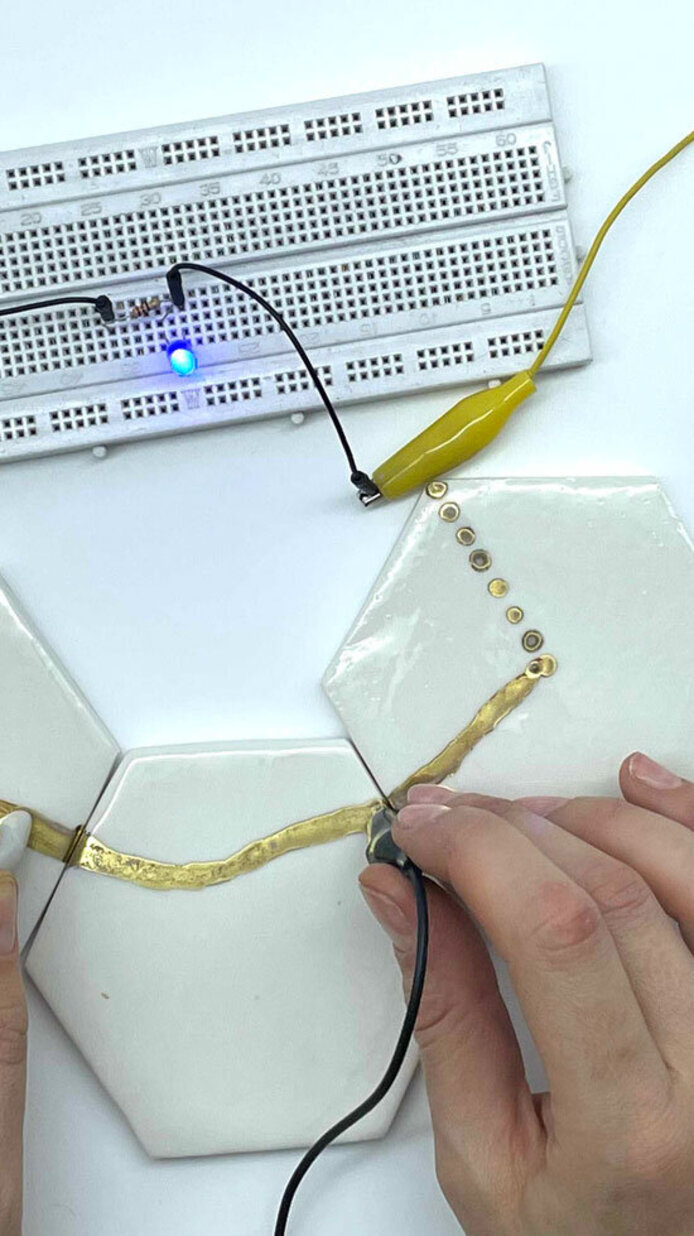

But her own research goes far beyond that. For years, she has investigated ways to produce electronics using exclusively recyclable materials. In her artistic research project “Feminist Hacking” funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), she and her colleague Patrícia J. Reis probe the question whether there can be such a thing as ethical hardware. According to their definition, this would include “technologies that do not harm the environment but instead use regenerative practices for the benefit of nature and humanity”.

Recycling must play a role in design and production

In a joint project, they developed a microcontroller made from 100% recycled fair-trade resources. It enables the construction of an interface that can turn various kinds of input such as analog or digital signals into movement, light or sound. But when the researchers try to roll out serial production of such products, they consistently encounter the same obstacle, Wuschitz shares: it is virtually impossible to find the same components in source products. “For recycling to be successful, it is therefore crucial that the ability to easily disassemble something into its components is already considered in the design and production stage,” the researcher stresses.

Using the young generation’s potential

Wuschitz’ and Reis’ Citizen Science project “Salon of Open Secrets” is based on this artistic research project and aims to make use of young people’s creative forces. “When crises abound, it’s often unorthodox approaches that suddenly render an idea conceivable. This is also why I enjoy working with lay people so much,” Wuschitz says about the benefits of Citizen Science projects, where participants are turned into researchers.

Workshops in the Vienna Technical Museum

In workshops held at the techLAB of the Vienna Technical Museum in early October, participants will be able to discover alternative technologies in a virtual game. As they navigate virtual landscapes, they will encounter the avatars of experts from all over the world who will tell them about the problematic background of mining certain metals and propose alternatives. In a next step, participants will assemble prototypes as part of small experiments undertaken in real life, which they will then present and discuss with the experts on an international online platform.

Successful initiatives from the Global South

The experts who will stand ready in these workshops are researchers from Germany, the US, Mexico, Cuba, Indonesia, Nepal, Singapore and Ghana. “Particularly the Global South has so many successful local initiatives to offer that the international community, unfortunately, fails to acknowledge,” Wuschitz points out a chief grievance. “This is why we need to strengthen the cooperation between researchers from Europe and the Global South even if the latter often do not publish their results in the usual journals,” she says. An example is the Ghana-based company “Dext”, which turns European e-waste into research kits to be used in schools. Engineer Gameli Adzaho organizes opportunities for encounter such as “science cafés” where young people and scientists from Ghana can get together. Saad Chinoy, a researcher from Singapore, devotes his time to blending electronics and nature. In the mud batteries he is working on, electricity is produced by microorganisms.

Paper loudspeakers and mud batteries

Several workshops with teenagers and children already took place in the spring of 2023, the creative output of which has been collected in the publicly accessible Gathering for Open Science Hardware (GOSH) wiki. Entries include fully functional loudspeakers made from paper, mud batteries and circuits on clay sheets. As a final step, the project will make manuals for the developed tools available to schools. What can be said about the collaboration with the young people so far? “The younger the kids, the more interesting their ideas. For instance, there were many ideas on how to communicate through plants,” Wuschitz shares.

Communication between science and the youth movement

One of Stefanie Wuschitz’ goals in her work is to enable communication between science and the youth movement. She says that “we want to make use of the creativity and transformative energy of young people and hope that the visions created this way will enhance our perceptions of future technologies and enable participants to imagine a different kind of future.” This will require democratic access to knowledge, which means that everybody’s values, goals and expectations must be heard. “It is high time that young people, who are particularly affected by the climate crisis, actively contribute to the public debate,” Wuschitz says about her motivations.

About the researcher

Stefanie Wuschitz’ work blends art, research and technology and has a special focus on critical media practices (feminist hacking, open source technology, peer production). She studied Media Arts at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and New York University (Tisch School of the Arts). In the course of her Digital Arts Fellowship at Umeå University in Sweden, she founded the queer-feminist collective Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory, which operates a feminist hackerspace in Vienna today.

She completed a doctoral thesis on feminist hackerspaces at the Vienna University of Technology in 2014. Wuschitz has held research and post-doc positions at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, the Vienna University of Technology, Michigan University and the Berlin University of the Arts. From fall 2023, she will hold the FWF-funded Elise Richter PEEK position at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. She continuously engages in artistic research, among other topics on digitalization and feminism in Indonesia. Her artwork has been featured in numerous exhibitions in Austria and abroad.