Byzantium: new insights into marginalized groups

The historical sources on marginalized groups are not really abundant. Pointers and evidence are widely scattered and often discovered in surprising places. One example is a letter by the scholar and courtier Michael Psellos, written around 1050 AD, in which he describes a sea journey on a merchant ship: “The description reveals that the fellow travellers listened openly and amid much laughter to a strange ascetic man, who told them which of the inns in Constantinople also offered the services of prostitutes. This is proof that it was possible at that time at least to address this illegal practice in public,” says Ewald Kislinger, a Byzantinist at the University of Vienna. In a research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, he and his colleague Despoina Ariantzi focused on three marginalized groups, namely tavern-keepers, actors and prostitutes, and made a comparative study of their respective situations. One of the findings: in the 11th century, social exclusion of these groups seems to have been less rigorous in parts of the Byzantine Empire. The prosperous economic situation was one of the reasons for this more tolerant attitude. “This more relaxed openness was probably also a consequence of increasing trade contacts with other cultures and the West. Some marginalized individuals benefited from this to varying degrees,” explains the researcher.

Challenging descriptions by outsiders

In terms of availability and scope of sources, both vary widely between the metropolises studied -- including Alexandria, Constantinople, Jerusalem or Thessalonica -- and rural areas, since chroniclers were rare in the provincial areas. At any rate, one can assume that the large cities of the huge empire, whose core areas in the Balkans and Asia Minor alone extended over one million square kilometres, offered better chances of a good life for fringe groups. But since written reports have always been written about them, they always describe their situation as seen from the outside. References to their everyday lives or social status can be found in various types of sources, with legal texts and hagiographies being central for the researchers in this respect. The latter, descriptions of the lives of saints, were aimed at educating a large audience and constitute a reflection of everyday life. In order to be able to distinguish between propaganda and facts in external representations, however, the researchers relied on criticism of sources, i.e. an assessment of the factual value of sources.

The fine line between legal and illegal

Now, what do these three marginalized groups have in common? Two things: their services were meant to entertain, and they all used taverns and lodging houses for their activities. In contrast to actors and prostitutes, however, the hospitality industry was not marginalized as such as long as the tavern-keepers contented themselves with the usual lawful services - food, drink, conviviality and accommodation. If, however, they had actors performing or offered the services of prostitutes, their reputation quickly plummeted and they were viewed with suspicion. The fact that women who were legally employed in the tavern often illegally practised prostitution for a sideline income shows just how small the gap between legal and illegal was.

The sources usually reveal nothing about how the courts dealt with such violations in practice. The temptation was great, nevertheless, to boost business with such additional entertainment services. Moreover, competition increased the pressure. “Pilgrims could find the goings-on in a traditional tavern offensive, which is why Christian guesthouses, so-called xenodochia, emerged,” notes Kislinger. A document from the archives of the monastic communities of Mount Athos speaks of such a guesthouse on a busy road and of how it came into the possession of the monks. Such competition between commercial and Christian hospitality services existed throughout the history of the Byzantine Empire.

Exclusion was hard to shed

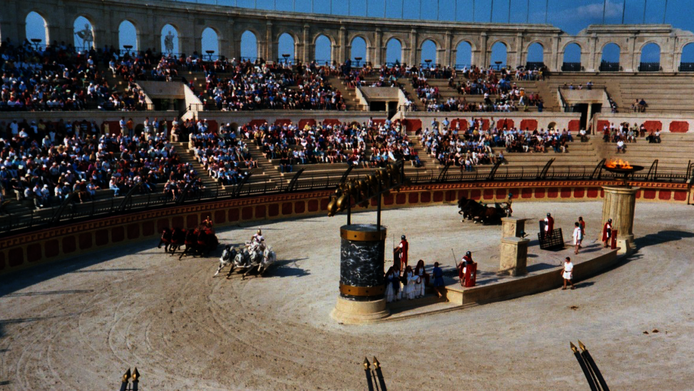

“Byzantine society had a fraught relationship to acting, which originated in classical theatre and was considered pagan. People found the mimes' activities dubious and the possibilities for appearances became increasingly restricted,” explains Kislinger. The elites disliked the performances because they were offensive, coarse and sexually charged or even obscene and ran counter to the strict Christian morals. In addition, the performers never hesitated to criticize and parody injustices or mock the authorities and Christian rites. Ultimately, they entertained their audience only in taverns, in the intermissions of chariot or horse races in the hippodrome or as jesters at the imperial court. Because they were such a scattered group, they were unable to shed this marginalization. The examples of the Eastern Roman Empress Theodora I, wife of Emperor Justinian I (6th century) and Saint Theodore of Sykeon (early 7th century) show for how long belonging to a marginal group was considered a flaw: as a young woman, Theodora worked as an actress, and the historian Prokop was unsympathetic to her. “He severely distorted her life in his work and even made her out to be a prostitute,” says Kislinger. St. Theodore, on the other hand, was derisively nicknamed Pornogennetos (whoreson) by his enemies, because his mother, whose family ran an inn, also worked as a prostitute there.

Breaking with clichés

Evidence of how some fringe groups benefited from the more open atmosphere in the 11th century can also be concealed by mockery. According to Kislinger, a speech by the abovementioned Psellos, for example, provides some indication that it was indeed possible to rise above the social milieu into which one was born: “The speech is about the son of an innkeeper who studied law and became a lawyer, but not a very successful one. Psellos mocks him by saying that the inn was flourishing, but the law books would not make him prosperous.” Although intended as criticism, this comment reveals to the researcher that tradespeople did indeed have the option of social advancement. In the face of testimonials such as these about how Byzantine society dealt with marginalized people and about the changes between the 6th and 12th centuries, the stereotypical image of Byzantium is clearly in need of revision.

Personal details Ewald Kislinger is a Byzantinist in the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies at the University of Vienna. He was one of the first researchers in Vienna to deal with everyday culture in Byzantium in the 1980s. Between 2007 and 2018 he was also editor of the Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik. His research focuses on event history, Byzantine Sicily and everyday life - material culture.

Publications