A tale of fake plumage and immaculate cookbooks

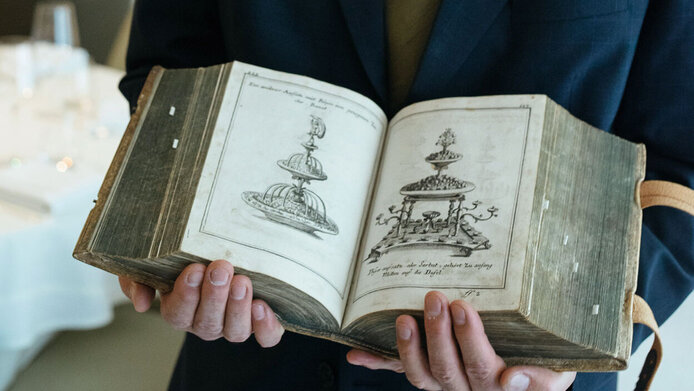

It is not only the contents of the baroque cookbooks in the Salzburg Provincial Archives that are surprising, but also the pristine state they are in. No grease stains, no dog-ears, no notes or favourite recipes where they immediately fall open. Until recently the head of the Gastrosophy Centre at the University of Salzburg’s History Department, Gerhard Ammerer knows why they are so well preserved. Between 1500 and 1800, cookbooks were still expensive representative objects. It took some wealth to be able to afford Conrad Hagger’s Neues Saltzburgisches Koch=Buch (New Salzburg Cookery Book), which dates back to 1718/19 and contains around 2500 recipes and 318 copperplate engravings. The only recipes that were written down concerned meals for festivities, and these were recorded for culinary professionals: “There was most probably a discussion about what was to be put on the table for the respective occasion, and perhaps the cook and the lady of the house browsed the volume, and afterwards it was put back in the bookcase.” For a team led by Gerhard Ammerer, many years of research into the history of food in the Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg culminated in the project “Food tradition and cultural transfer in Salzburg. The Example of the Prince-Archiepiscopal City of Salzburg, 1500–1800”.

Good sources across all strata of society

For this medium-sized town in the early modern period, the researchers succeeded in tracing what was put on the table and how food was obtained and distributed – across the board from the archiepiscopal residence to taverns and inns and soup kitchens for the poor. Ammerer notes that there are excellent sources for all social strata. Being an economically important household, buyer, employer and benefactor, the Prince-Archbishop’s court has furnished the richest sources. But there is also good documentation about the guilds, the bourgeoisie, the monasteries, as well as poorhouses. Thanks to charity on the part of the church, even poorhouses were able to serve fine venison and beer on church holidays. Cuisine for lent and fasting periods was also sophisticated. After all, fasting was practised on more than 80 days during the year. The menu often featured sweet dishes, but also home-grown turtles.

Trends, ingredients and showy dishes

The court in Versailles and Italian courts were models of dining culture for the prince-archiepiscopal city of Salzburg and the bourgeoisie in turn emulated the archiepiscopal court. Trends found their way into Salzburg through the exchange of cooks and recipes. During the period under investigation, one striking feature was the increasing consumption of Mediterranean citrus fruits and almonds, which was made possible by the lively north-south trade with the Adriatic region. Cooks also made use of an increasingly diverse range of spices, such as mace. Around 1600 there were around 200 servants and staff individuals with the right to eat at the Prince-Archbishop’s court. Consumption included 600 litres of wine that were served at the tables every day – and that figure was growing.

Sources from the Baroque period that enlighten us about what was served include court regulations, salary lists, recipes, letters and registers of wine stocks. While food was frequently used for representation, thrift was often preached as well: “Conrad Hagger’s cookery book, for example, includes the illustration of a wire rack which could be used to put the plumage back to cover the finished roast. The showy dishes were intended to impress guests, and some things were not eaten at all. The menu was plentiful, especially on holidays, but nothing was thrown away; leftovers were given to the servants on the lower ranks of the hierarchy as ‘scraps’.”

Sources that turned out to be exciting for the research team in Salzburg included two notebooks kept by Johann Ambros Elixhauser, the innkeeper of the Stieglbräu, a medium-sized inn. Starting in 1756 he kept notes for decades on all the celebrations and festivities that took place at his inn, recording the occasion, the number of people, the food and drinks prepared, and the costs. Students celebrated their graduation at the Stieglbräu, priests their ordinations, and guilds held their annual assemblies there: the entries inform us that “rich” professions such as goldsmiths or brewers were able to celebrate more lavishly than “poor” ones such as fishermen.

Exchanging recipes by mail

Overall it can be said that the period between 1500 and 1800 saw a refinement of cuisine and table manners. More and more aspects were regulated in rules issued by the court, the guilds and market authorities which determined where and how people were allowed to eat. An increasing number of people were occupied full time securing the provision of food. A great deal of information about recipes or the quality of restaurants was also exchanged by post between courts and between citizens of different states. Numerous letters have been preserved from the travels of the Mozart family that tell us what was available to eat and drink in which places in Europe – and what was not. Items that Ammerer and his team did not find in the archives are today’s Salzburg cuisine classics such as Mozartkugeln or Salzburger Nockerl.

Personal details

Gerhard Ammerer studied history, German studies and law at the Universities of Salzburg and Innsbruck. In 2000 he acquired his professorial qualification at the University of Salzburg for the subject “Austrian History”, and in 2009 for the subject “History of Law”. Between 2014 and 2020 he was head of the Gastrosophy Centre and, until 2023, of the “Gastrosophical Sciences” study course. In 2015, Ammerer became a member of the Commission for the Legal History of Austria of the Academy of Sciences. The three-year project “Regional Food and Cultural Transfer: Salzburg 1500-1800” was funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF with EUR 348,000 euros and extended by the citizen-science project “Salzburg zu Tisch”.

Publications and contributions

Gerhard Ammerer, Ingonda Hannesschläger, Martin Holý (eds.): Festvorbereitung – Die Planung höfischer und bürgerlicher Feste in Mitteleuropa 1500–1900, Leipziger Universitätsverlag 2021

Gerhard Ammerer, Michael Brauer u. Marlene Ernst: Barocke Kochkunst heute. Das Adelskochbuch der Maria Clara Dückher, Anton Pustet, Salzburg 2020

Buchreihe „Gastrosophische Bibliothek“, 8 volumes, Mandelbaum Verlag Wien–Berlin