A bigger role for women in science

The Austrian Science Fund FWF is working to strengthen the position of women in the scholarly community and has pursued relevant policies for about 30 years. A catch-up process has taken place during this period, and an impressive distance has been covered on the road to gender equality. As a result, the numbers of highly qualified women scientists have grown to unprecedented levels. FWF introduced its first programme for the advancement of women in 1992, followed by a programme for young women scientists in the early stage of their careers in 1998 (see “Mobility programmes and promotion of women in retrospect”). When the programmes started, only 4.5 per cent of professors were women, a proportion that has since then grown to 25 per cent. Policies aimed at promoting women researchers were further improved and expanded to a two-stage programme in 2005, when a new funding scheme was launched for women on their way to a professorship to effectively support the long-term establishment of women scholars at universities and other research institutions.

Fifty-fifty in early career stages

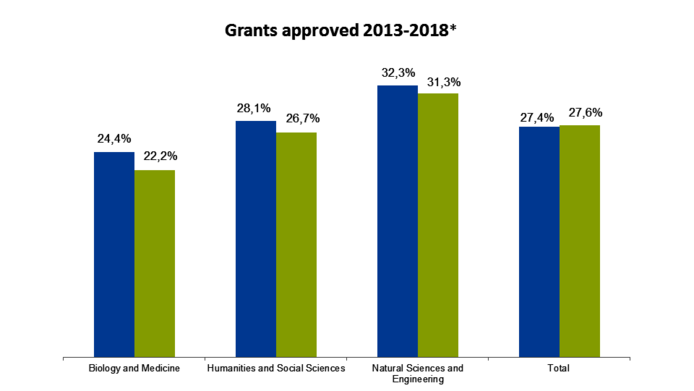

In retrospect, we see that FWF’s gender mainstreaming approach (most recently presented in the FWF Strategy for Gender Equality and Diversity of Researchers) and our specific policies for the promotion of women have been effective and successful. It should be noted in this context that other European funding organisations have not instituted comparable promotion programmes covering different stages in women’s careers. Rather, they focus exclusively on quality as a decision-making criterion, coupled with gender monitoring to uncover any distorted views or subconscious attitudes. The results of targeted promotion of women speak for themselves: At present, 34 per cent of all researchers applying for FWF funding are women. For scholars in the early stages of their career (within eight years of attaining a doctoral degree), the share is 45 per cent. The approval rate also stands at 45 per cent. Based on these numbers, we have concluded that by keeping the dropout rates of young women researchers low, we are moving faster and more effectively towards the goal of gender equality. Within its remit as a funding organisation, FWF has thus been able to achieve very positive results. In comparison with Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), FWF attracts a higher share of women applicants, and there are just as many women and men among top-level researchers in Austria. The number of women is rising with particular speed in the life sciences, whereas men still dominate in natural sciences and engineering. Breaking down FWF’s overall approval rates by gender, however, we find that women’s applications are equally successful as those of men.

Taking diversity seriously

These developments point to two main aspects: Three decades of active promotion policies for women have clearly increased women’s opportunities in science and made the potential of young talents more visible. Women researchers are more successful than ever in raising third-party funds for basic research. As a result, three out of five women are still active in research five years after the end of a project, as a recent study of the careers of project leaders under the Hertha Firnberg and Elise Richter Programmes has shown. The specific actions taken through the FWF’s programmes for women are clearly effective. These also include our decades-long assistance in developing networks among women researchers – efforts which FWF has pursued more actively than any other funding organisation. More women than in the past are reaching top positions, about one third (34 per cent) are holding professorships now. Interestingly, the average birth rate of 1.6 children among women researchers who receive FWF funding is slightly above the Austrian average of 1.5. This stands in contrast to the fact that women academics in general have fewer children than the national average. The numbers are proof that concrete gender equality policies are both necessary and effective, a conclusion that has also been drawn in a recent report of the Austrian Ministry of Education, Science and Research.

50 per cent quota to be introduced

Looking at these positive trends against the background of the status quo in the academic system, we find, in the words of a former Richter Programme participant, that “a programme is sustainable only if and to the extent that universities are committed to open up further opportunities for women.” What this means is: for gender equality to happen, we need the support of the research institutions. Programme evaluation reports commissioned by FWF have come to the same conclusion, as has a paper by the Science Europe Working Group, which states that collaboration between funding organisations and research institutions is necessary to help researchers become permanently established in science. These joint efforts to achieve greater gender equality and diversity will play a central role in our upcoming programme review to ensure equal access to FWF programmes for women and men in future.

New approaches in career development support and promotion policies for women

We believe that with the upcoming review process, FWF is taking a necessary step forward in its continuous efforts to provide researchers with adequate funding, which ensures predictability of resources and hence room for unconstrained scholarly development, two prerequisites for top-flight research that is competitive at the international level. Policies for the promotion of women must remain key and will be lifted to a new level: FWF has made a commitment to allocate half of its funds to women researchers and to make sure that men’s approval rates do not exceed women’s. Based on current statistics, FWF hopes that within a few years, these quotas will serve as a monitoring tool only, but will no longer be actually needed. We clearly have a large enough pool of excellent women researchers. More funding than ever will be available to them, being explicitly reserved for women.

Gender mainstreaming

Gender equality standards were introduced by FWF in 2005. Application statistics and approval rates are published annually, broken down by gender, and specific actions are taken to address the challenges faced by women researchers in the national scholarly community. Moreover, FWF implemented the necessary focus on the gender dimension in research approaches when introducing revised guidelines for all programmes in 2017. A 2018 Strategy paper on gender equality and diversity presents FWF’s vision and policies in this area.

More funding, more flexibility

The proposed two-stage programme for career paths in research that has been included in the current strategy for the period 2019–2021 will constitute the next forward-looking measure to raise the number of women in top positions in Austrian research. We are implementing this in close cooperation with Austrian research institutions. More funding also means that more women will be eligible for grants. By adjusting our funding portfolio, we will ensure that the best talent will join Austria’s scientific community. The next development step will strengthen FWF career programmes financially and further optimise framework conditions, including more diversity and flexibility. We will no longer differentiate our programmes by target group (such as women, incoming, reintegration) or programme goal (such as return to research work, brain gain, group-building), effectively eliminating any differences in the reputation of individual programmes.

At the same time, best-practice instruments will continue to be included in our programme portfolio. These include lump-sum payments for young mothers, active networking support, coaching workshops and policies to spotlight successful women. In the context of these plans, FWF has launched a consultation process in early 2019, which included a meeting with women holding positions under the Elise Richter Programme. The process, which involves several working groups and draws on the expertise of international experts, will be concluded by year-end.

Gender relations at the international level

A look at the world map shows that the status quo of gender equality differs widely across the globe. For example, the proportion of women in science in western industrialised countries such as Japan (20 per cent) is clearly lower than in Latin American countries such as Brazil (49 per cent). In Europe, the proportion of women in science has most recently climbed to 41 per cent, as the Elsevier study Gender in the Global Research Landscape has found. One fact has become abundantly clear: Breaking up entrenched gender roles requires an encouraging environment and structural change. In other words, effective changes can be achieved if diversity is taken just as seriously as other goals. Diversity in research engenders new ideas and perspectives, fosters group creativity and contributes to new views on research topics. Gender equality is a central component of diversity. FWF, the research institutions and many governments are aware of their responsibility in this respect. The Global Research Council – the umbrella organisation of research funding organisations worldwide – and the European Research Council have committed themselves to promoting equal opportunity in research. Gender equality and the empowerment of girls and women has also been defined as one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Barbara Zimmermann is an archaeologist and head of FWF’s Strategy – Career Development department. Prior to taking up her current position in 2004, she conducted late Antiquity archaeological research and research into the art history of Antiquity in Vienna and Rome and received a doctorate in her field.

Mobility programmes and promotion of women in retrospect

As early as 1985, the Austrian Science Fund FWF launched the Erwin Schrödinger outgoing programme as its first postdoc grant programme, which assists young scientists to work at a foreign research institution for up to two years. The Schrödinger programme is not only the FWF’s longest-standing postdoc programme, but also a particular success story. It was evaluated twice, and the resulting recommendations were implemented to ensure sustainable effects on careers in research. More than half of all former Schrödinger fellows are professors twelve years after their scholarships. The promotion of mobility was further strengthened in 1992 by the launch of the Lise Meitner incoming programme, which aims at brain gain for Austria through international cooperation. Since 2017, the programme has also been available to returning researchers.

Secure sustainable careers

FWF introduced the Charlotte Bühler Habilitation scholarship in 1992 as a programme for the promotion of women, to grow the female potential in science and raise the number of women who hold professorships or other high-ranking positions in science and research. The launch of the Hertha Firnberg programme, which assists women in the early stages of their research careers, followed a few years later, in 1998. At the time, only 4.5 per cent of professors were women – since then, their share has grown to about 25 per cent. The Charlotte Bühler scholarship programme was replaced by the Elise Richter programme in 2005, completing FWF’s two-stage career development programmes for women. The proportion of women applicants has grown to 34 per cent since then.