The social fever curve of coronavirus

On 25 February 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was detected in Austria for the first time. Two days later, in the plenary session of parliament, the government was still warning against any panic-mongering. The number of infections increased exponentially, however, both nationally and internationally, and on 11 March the WHO categorised the crisis as a pandemic. One day later Austria saw its first Covid-19 fatality. On 16 March, the Federal Government decreed a comprehensive lockdown and Austria closed up. People in panic-buying mode before the shops closed down added an uncanny touch to this extraordinary event. Press conference followed upon press conference. Pictures from Bergamo in Italy showed dramatic scenes: a convoy of military trucks transporting countless coffins through deserted streets in the middle of the night. The Austrian Federal Chancellor tapped into this image and fanned general anxiety: “Soon we will have a situation in Austria, too, where everyone knows someone who has died of Corona.”

The Austrian population largely complied with the prescribed restrictions and people reassured and encouraged each other. And courage was sorely needed in the face of an economic slump: in May, unemployment was at 12 percent, a record level since 1945, and one in three employees was on a reduced working-hours schedule. The Federal Government launched an omnipresent campaign: “Take good care of yourself, stay home. That’s how we all stay safe.” Every night at 6 pm, the Radio Wien channel played Austria’s unofficial anthem, the hit song I am from Austria by Rainhard Fendrich. Even the police in Vienna got in on the act and blasted the song through the loudspeakers of their police cars. People stood together and gave rounds of applause to the “relevant workers” in health care, food retail, delivery services and waste management. It was a time of anxiety, but also of confidence that this crisis would soon be over if everybody cooperated.

Crisis as an opportunity

The futurologist Matthias Horx even saw the crisis as an opportunity for society to turn over a new leaf. Some people hoped that this pandemic might herald a change of direction towards more sustainability and environmental protection. Indeed, the impact of the lockdowns started to become apparent: traffic in Germany fell by 23 percent, which was also measurably reflected in improved air quality. For May, studies showed a 17 percent reduction in global CO2 emissions in a year-on-year comparison. The widespread cessation of pleasure cruises and ferry traffic was improving the water quality in many places and, in April 2020, euphoric reports from Trieste announced that dolphins were seen frolicking in the harbour basin for the first time in many years. Would a virus be able to achieve what countless warnings of climate researchers had failed to do?

The social divide has become more accentuated

Today, nine months and two lockdowns later, there is not a great deal left of this optimistic mindset. “Hopes have been dashed,” notes Bernhard Kittel, a social scientist at the University of Vienna. “The crisis has accelerated the widening of the social divide that we have been observing for years. The division of society has become more pronounced, solidarity has declined, and so has people’s trust in the government and democracy,” Kittel concludes. He has extensive data to back up this sobering diagnosis.

Polling 1,500 people every month

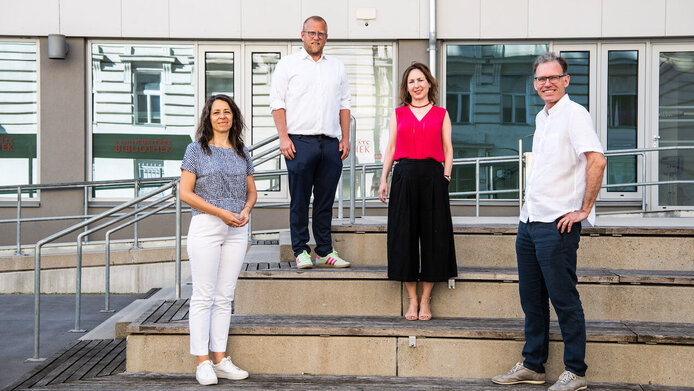

Together with his colleagues Sylvia Kritzinger, Barbara Prainsack and Hajo Boomgaarden and a multidisciplinary team, Kittel is exploring attitudes, behaviour and reactions to the corona crisis of people living in Austria. The Austrian Corona Panel is one of the largest social-science corona studies in Austria – 1,500 people are polled every month to obtain sound data that helps the researchers answer many questions. How are people dealing with the threat to their health and economic wellbeing? What do they think about the pandemic and the measures to overcome the crisis? Which groups are particularly affected? Are we seeing a change in attitudes towards democracy and the rule of law?

Duration of the pandemic was underestimated

When the FWF granted him urgent funding in July 2020, Kittel was able to continue his study, which had already been started with seed-funding from the Vienna Science and Technology Fund WWTF at the end of March. He wrote the application for the WWTF’s short-term call for proposals in one night. “Then the five of us worked non-stop through a weekend to design the first questionnaire,” Kittel recalls in talking about the start of his project. Just two weeks after the first lockdown was announced in March, his team were already out in the field. But even the researchers had underestimated how long the crisis would be. One question in the first questionnaire asked for people’s views on how long the crisis would last. The highest value one could select was “longer than 6 months”. Only a few respondents thought that it would take that long.

Optimism that it will soon be over

According to Kittel, this optimistic view that it would soon be over was one of the reasons why the government’s measures enjoyed such a high level of popular support in the first few weeks – informed by a spirit of “let’s buckle down and get it over with”. The horror scenario painted by the Federal Chancellor and the images from Northern Italy also played a decisive role in this context. “Moreover, this was a novel and historic experience for our generation,” says Kittel when describing the sentiment many people had in the spring. People took the virus seriously and complied with the prescribed measures, even if it was for a range of different reasons: to protect themselves, to protect others, because it constitutes a clear social – as well as legal – norm.

Failed communication strategy

The relaxation of restrictions at the beginning of the summer gave people the impression that it was in the bag now – even though all the forecasts in May already indicated that the situation would deteriorate in the autumn. Kittel sees this as a failed communication strategy: “In advisory circles close to the government it was known at that time that we would be in this pandemic for many more months. The ‘we’ve done it’ communication strategy gave the wrong spin and ultimately contributed to the rise of infections in September and the skyrocketing numbers in October,” says Kittel, commenting on the dynamics of the process.

One in three people is dissatisfied

The data collected by the Austrian Corona Panel make one thing utterly clear: individual support for corona measures depends largely on how much trust someone places in political institutions. The greater the trust in the government, the greater the readiness to comply with the regulations. This circumstance is one of the reasons why lockdown no. 2 feels completely different from lockdown no. 1. The health and economic risks are considered to be as high now as at the beginning of the pandemic, but only ten percent were dissatisfied at the end of March, while the number is 33 percent now. Only half of those surveyed are satisfied with the government’s efforts, and the vast majority profess to be “rather satisfied” rather than “very satisfied”. Only 10 percent are “very satisfied”. “If less than half of the population is satisfied with the work of the government, that is a warning signal,” notes Kittel, and he spells it out: “That represents a tripling of dissatisfaction within half a year.”

Solidarity takes a dive and the short-time work scheme is helpful

Another development that Kittel can read clearly from his data is the decline in solidarity. Whereas in March, 62 percent of respondents said they believed that social cohesion had increased because of the crisis, this value has steadily decreased from one survey wave to the next and currently stands at 14 percent. Those who already had a hard time before are particularly hard hit by the crisis: single parents, who are almost exclusively women, single-person enterprises and freelancers, as well as pupils from socially disadvantaged families. People who lost their jobs during the crisis are also severely affected.

In terms of psychological strain on the unemployed, the data clearly show that the tendency towards depression has risen sharply in line with job loss. This connection between work and the tendency to develop depression also works in the other direction, however: those who got a job during the crisis – especially in the sectors that have been booming since the lockdown, such as parcel delivery – suddenly fared better in psychological terms. People who worked under a reduced working-hours scheme during the first lockdown – one in four employees, no less – remained comparatively stable. “The short-time work scheme has saved many people from psychological problems,” says Kittel.

The crisis highlights the problems at school

According to Kittel, the pandemic has exacerbated and accelerated a development he has been observing for years – an accentuation of societal division along the lines of education and labour market opportunities: “It illustrates the miserable situation we have seen in our schools for decades, brought about by the fact that the major political camps in the Second Republic kept blocking each others’ efforts.” Kittel gives an example: “In primary schools in Vienna, the difference between the best and the worst pupils is tantamount to several years of acquired learning. Something is going fundamentally wrong here. This prevents opportunities for development and leads to ever more marked dividing lines in society.”

Massive support required

We would need massive support for socially disadvantaged pupils who were already neglected before the crisis. This calls for educational and social policy action. However, in view of the rigorous austerity measures which the Austrian population will be facing, Kittel fears that these problems will not be given priority. “This means that we are seeing a generation growing up that is divided even more strongly when it comes to opportunities, where many will be left behind. But these problems will only become properly noticeable in the coming months and years.”

Loss of collective element in record time

Another development which Kittel views with concern is the increasing scepticism towards democracy. This is another area where the corona pandemic has accelerated a development: “The changes we have seen between March and November reach an order of magnitude that would otherwise emerge over a period of perhaps five to ten years.” Kittel points out that in the last 30 years the liberalisation of the financial markets has already led to a widening gap in income and wealth, and this has been accompanied by some groups becoming disconnected from social participation and by a radicalisation of considerable portions of the population. “This is increasingly leading to a situation where the collective element – i.e. social solidarity and integration – gets lost,” warns Kittel.

Only one in three people want the vaccine

Since the beginning of the corona pandemic, scientists throughout the world have been working at full speed to develop a vaccine that will allow us to return to our old lives. There is light at the end of the tunnel and the first vaccination campaign is due to start in Austria at the end of 2020. But Kittel’s figures speak a clear language: the readiness to receive the vaccine has dropped sharply between May and October 2020: in May 2020, about half of the population wanted to be vaccinated as soon as possible, whereas this share had dropped to one third by October 2020. Those who are opposed to vaccination in general are even more deeply sceptical now.

Being ready to get the vaccine not only depends on how someone perceives their own personal vulnerability, or on age and gender, but also on how satisfied they are with the government’s performance. Older people, men, the more highly educated and those whose political stance is left of centre tend to be more willing to be vaccinated. Being much more severely affected by the additional burden of the crisis because of care and family obligations and home schooling, women are generally more dissatisfied and tend to be less willing to be vaccinated. Individuals who have concluded an apprenticeship – who are more affected by unemployment – are also more dissatisfied and more reluctant to get the vaccine. The most pronounced opposition to the vaccine, however, is found among the declared non-voters. “These are people who no longer see themselves as being part of society,” Kittel points out.

Facebook instead of quality media

The willingness to be vaccinated against Covid-19 also depends on where and how people get information and what media they consider relevant. Kittel describes the results of the study as “shocking”: “There is a very clear-cut differentiation according to level of education, whether someone consults quality media, or just Facebook entries and Instagram posts.” Measures to fight the pandemic are dividing the population, and at the same time the willingness to get a vaccination that will keep one protected and help to overcome the crisis is decreasing. This is a paradoxical and disquieting development. So what should be done?

Discussion in society instead of message control

“We need a broad-based societal debate,” Kittel says. According to the sociologist, many people are insecure because at the moment we do not know a great deal about the vaccines that were produced in record time. That the novel RNA vaccine allegedly causes cancer is just one of the rumours circulating on social networks. We need this to be taken up in discussions. Kittel identifies an omission in government communication: “The discourse has shifted to the social media, where conspiracy theories, unsubstantiated opinions and ‘alternative facts’ are given the same status as scientifically proven statements. These are the disastrous consequences of a type of communication that relies on message control instead of stimulating societal debate and confronting this debate on an equal footing.”

Finding societal consensus

One possible strategy is to conduct what is called “deliberative opinion polling”. Especially in the case of socially highly controversial issues this method can lead to sustainable solutions, because they are supported by a substantial portion of the population. The method relies on setting up a representative sample of the population and engaging them in a debate together with various experts. In a transparent discursive process that is supported by the media, the participants develop answers to the question of how society should deal with the crisis from the multitude of divergent opinions. The benefit: everyone sees their interests represented in the sample group, which gives the solution a substantial basis in the population. The most famous example of using this method to arrive at a social consensus was the issue of abortion in Ireland, a highly controversial issue in this strictly Catholic country. After the deliberative polling process, the Irish people voted to lift the ban on abortion on 25 May 2018. “Even though there are still some people who are opposed to the solution, society has found agreement through this process”, Kittel notes as he recounts this successful example of democratic political decision-making.

“It’s never too late to discuss things”

Kittel is convinced that if this process had been carried out in Austria during the summer months, it would have been possible to arrive at a societal consensus on many issues by September. Why was this path not taken? “This process would have had to be funded and control would have been relinquished. This is not in line with the strategy of our government,” Kittel points out. But what must policy-makers do to regain the trust of the population? “It is never too late to discuss things,” Bernhard Kittel posits. “In such a situation, everyone would have to abandon their partisan stances and their competitive manoeuvring and focus on solutions.”

Is there hope for the environment?

The approval of several vaccines being imminent, there is hope for an end to the pandemic – provided that enough people agree to be vaccinated. But what about the hope for a changing outlook on climate protection? In Brazil, overshadowed by the pandemic, the rainforest is being cleared at a pace not seen for twelve years. Three football pitches of jungle disappear every single minute. Satellite images taken by the Brazilian space agency INPE (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais) show that forest clearing in June 2020 has increased by almost 11 % compared to the same period in 2019. Between August 2019 and July 2020, forest clearing destroyed a total of 11,000 square kilometres of rainforest. These figures speak for themselves. As do others: the number of heaters for outdoor seating at bars and restaurants, for instance, that has skyrocketed in Austria in October – a trend that is fuelled even further by the distancing requirement. For sustainability to be consistently pursued, we seem to need more than a virus, after all.

Personal details

Bernhard Kittel, a political scientist and sociologist, was one of the first researchers to receive urgent funding from the FWF in August 2020, which cemented the continued funding of his Austrian Corona Panel. He began work on this project, the largest social-science corona study in Austria, at the end of March. Since then, 1,500 people – a representative sample of Austria’s population – have been polled every month, providing data on important questions about how to handle the crisis.

Born in Vienna, 53-year-old Bernhard Kittel grew up in Switzerland and the Netherlands, studied political science at the University of Vienna and, after completing his doctorate, received a Master’s degree in Social Science Data Analysis from the University of Essex, United Kingdom. He conducted research at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, was Junior Professor of Social Policy at the University of Bremen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and Professor of Methods of Empirical Social Research at the University of Oldenburg, where he also served as Founding Dean of the Faculty of Educational and Social Sciences from 2008 to 2010. In March 2012 Bernhard Kittel was appointed Professor of Economic Sociology and Head of the Department of Economic Sociology at the University of Vienna.