Australian microfossils in Milan

I am an earth scientist, and currently I am enjoying my Schrödinger Fellowship return phase at the University of Vienna, where I am conducting research on the responses of unicellular marine microorganisms to environmental changes during extreme climate phases in the Cretaceous period. A decisive moment in my career occurred a few years ago, when I was presented the opportunity to work in the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). It became clear to me that an international dimension is indispensable and should have a constant role to play in research and in my own professional life.

Having completed my doctorate at the University of Vienna, I was in no doubt that I wanted to build on the experience I had gathered in individual international collaboration projects. Taking part in an IODP expedition off Australia's west coast furnished new contacts. In Australia, we recovered sediment cores from the Cretaceous period, and the next steps followed quite naturally from this. At this point I knew that I wanted to do postdoctoral research on microfossils in prehistoric climate change in Maria Rose Petrizzo's research group at the University of Milan.

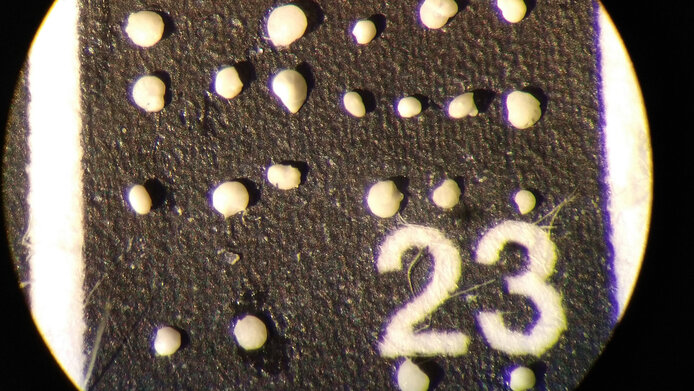

Witnesses of Cretaceous climate change under the microscope

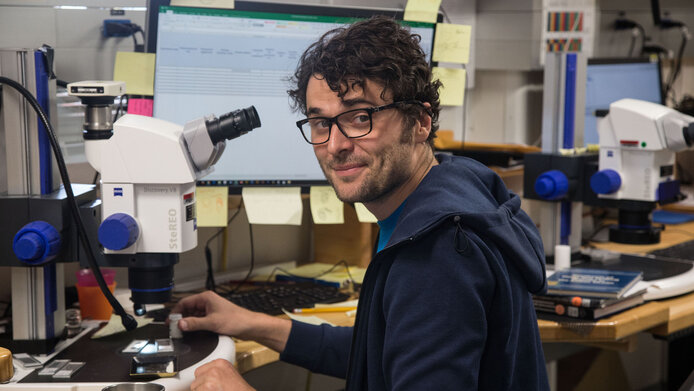

Once the exciting part of collecting sediment samples has been completed, most of my day-to-day work as a geologist (micropalaeontologist) takes place in front of my microscope and the computer screen. Basically, this work involves the processing of sediment samples and, of course, the analysis of changes in the population structure of fossil marker species, which provide us with clues about the environmental conditions more than 65 million years ago.

At the beginning of my stay abroad in 2020 the pandemic was still raging and the associated contact restrictions impacted my work considerably. Like almost everywhere else in Europe, the university in Milan allowed only limited activities for a long time, which mainly meant that exchanges with colleagues were nonexistent. For almost two years, that also made it impossible to meet up at conferences or other universities.

But even if the conditions at the beginning of my Schrödinger stay were less than ideal, I am very pleased with my scientific output during that time. The stay abroad gave me the opportunity to help gain a better understanding of prehistoric extreme climates. Even if by no means all aspects of climate change in the Mesozoic era apply to the current situation, the results of the last three years whet our scientific appetite for more discoveries and provide numerous starting points for further research projects. These are some of the issues at hand: to what extent can we consider prehistoric extreme climate phases as a template for current processes? What can we learn from the development of benthic habitats during the Cretaceous period?

Milan and the surrounding area

During the time I was able to spend in Milan as part of my Schrödinger period abroad, I experienced the city as a welcoming, livable city. Apart from the well-known attractions such as the Duomo, Da Vinci's Last Supper and Fashion Week, Milan has a lot to offer and never gets boring. Given its central location in the Po Valley, between the Alps in the north and the allure of the Ligurian Riviera in the south, the region still offers many things for me to discover. Despite my long stay I was not able to explore to the full the city of Milan or the region of Lombardy. In the area around Milan in particular, almost every town holds some attraction – from Roman columns and mosaics to medieval churches and castles. Hence, there is still a lot of exploring to do.