Blurring borders

“The support for artistic research provided by the Elise-Richter-PEEK programme is just unique”, says Lucie Strecker enthusiastically about the FWF grant she received at the end of 2015. In the context of funded university research she finds it easier to alter content-related borders and engage in transdisciplinary basic research.

Cooperation with medicine

Based at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, her project The Performative Biofact has been running since the beginning of the year. For the project, Lucie Strecker cooperates with the Medical University of Vienna (MedUni Wien) within the programme Arts in Medicine, which she co-founded with the medical professional and artist Klaus Spiess with whom Strecker has been collaborating since 2009.

Where is the borderline between nature and technology?

While based on earlier work by Strecker, this Elise-Richter-PEEK project focuses on the transformation of materiality. Strecker starts from the assumption that our understanding of materiality is constantly transformed and developed by our actions. Given that the life sciences fundamentally change our views of nature and ecology, the artist believes that the distinction between nature and technology, between growing and non-growing things, is no longer valid: living creatures are no longer unambiguously part of the natural world, once the methods employed by agricultural and biotechnical sciences have imbued them with artificial or technical facets. “This also changes our self-view and our anthropocentric world view”, Strecker points out. But hasn’t humanity repeatedly been confronted by technical change? The difference between current and former change is what the artist focuses on in her work. “This is what the science historian Hans-Jörg Rheinberger says about the history of genetics: There is a point where technological changes in biological material make it become technology. This is the point I’m interested in”, notes Strecker.

Biofact – between animate and inanimate

In her Elise-Richter-PEEK project she seeks to create an entity whose ontological status oscillates between the animate and the inanimate. The biologist and philosopher Nicole C. Karafyllis coined the term “biofacts” for such entities. In her current work, Strecker is going to explore how technological innovation will change our understanding of ecology and art in the future. In this context, the artist examines historical relics of cultural relevance. Strecker emphasises that it is important to dissipate the anthropocentric view through involving animals and creates new biofacts from animal matter. An example of such a relic that Lucie Strecker and Klaus Spiess used in their performance The Hour of the Analyst Dog is a woollen blanket into which Anna Freud wove hair from her father Sigmund Freud’s Chow dog that was on hand at his master’s psychoanalysis sessions for many years. Together with researchers from the domain of life sciences, Strecker intends to develop experimental arrangements that blend methods from archaeology, performance, molecular biology and genetics.

“I am a director”

In her work, Lucie Strecker always takes care not to become hostile to technology, but to approach her themes with utmost openness. “Being neither a social scientist, nor an expert in ethics or biology, I see myself in the capacity of a director who induces other voices to speak, who creates situations that make things become visible. I enable and stage dialogue”, is how she describes her function.

From dance …

This kind of openness can also be found in her biography. At the young age of seven the Berlin-born Strecker started dancing and participated in the professional training of young dancers at the Deutsche Oper Berlin. A life that included many hours of training every day and numerous performances. There was hardly time for anything else. As a teenager, her curiosity for the world out there became stronger and the opera world seemed narrower and narrower. At the age of 16, Lucie Strecker finally decided not to pursue a career as a dancer.

to the visual arts, …

Under the influence of her grandfather's paintings, the artist, now aged 39, embarked initially on visual arts courses and started to study visual arts at the Berlin Weißensee School of Art. Under the sway of the visual arts, choreography and dance she increasingly felt the need to deal with technical questions relating to performance. What distinguishes a visual arts performer from an actor? What is the role played by spoken language?

to directing …

In 2005, Strecker applied for admission to the Max Reinhardt Seminar acting school, and moved to Vienna upon being accepted there. During the application period she realised she was expecting a baby, her daughter, who is now 11. A grant from the German Academic Exchange Service, a merit-based scholarship, a grant from the Tokyo Foundation plus a student loan enabled her to graduate from her stage directing course.

and art research

She concluded her third round of university studies at the Berlin University of the Arts, an alternative to a PhD, which provides artists with a two-year grant enabling them to do art research and obtain the degree of a fellow at the Berlin University of the Arts. Lucie Strecker says meeting Klaus Spiess was a key moment in her career trajectory. They have formed a continuous collaboration involving exhibitions, publications, lectures and live performances in the realm between art and science. One of the last shared projects was Hare‘s Blood + in 2015.

Hare’s blood

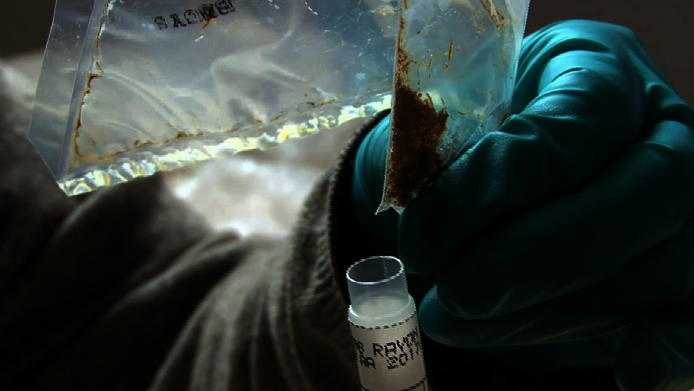

This piece sprung from the question as to where one could get a biological relic that was already being traded on the art market. They chose Hare’s Blood, an artist multiple by Joseph Beuys from 1972, in which he had sealed 4 cl. of hare’s blood in a triangular plastic bag. Why blood from a hare? “In the Middle Ages, cloth dipped in hare’s blood was sold as a remedy for certain illnesses and mental disorders such as ‘being obsessed’. The hare was seen as a vagabond between the worlds, a companion on the journey between life and death. There are several interpretations for the triangular symbol. A triangular mirror was considered a gateway to the beyond: an abstract symbol representing genitals? It is also often said that in Beuys’ work the geometrical represents the inorganic world, and blood, for instance, the organic world. These dualities can be found in his work very often”, Lucie Strecker says in assessing Beuys‘ multiple.

Hare‘s Blood +

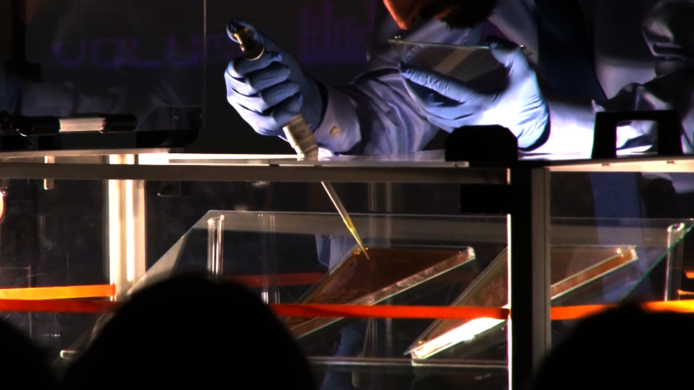

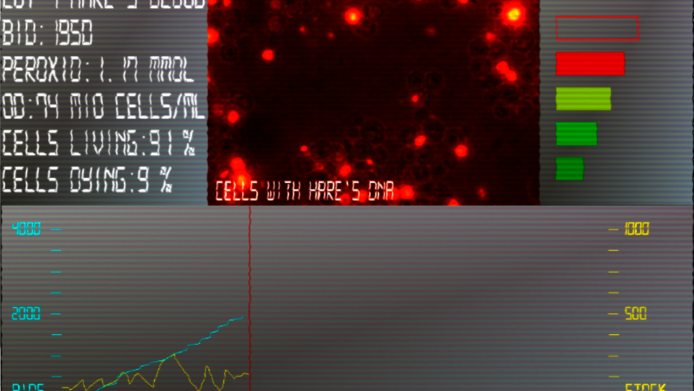

The first step in the project was a telephone call to the art dealer. “I asked him whether he believed it was really hare’s blood. Even this request for proof was really a provocation”, relates Strecker. The art dealer replied that if it was not hare’s blood it would severely shake his confidence in Joseph Beuys. The next step was buying the art object online, representing the “embedding in a global market economy”. “We then went looking for a situation where bio-technology, the material itself and an audience would all be confronted in an economic context and lead to unpredictable reactions”, as Strecker recalls the process. An auction was the site of choice. They fashioned a petri dish of the same format as the triangular plastic bag. In this copy, the scientists developed a catalase switch using yeast and a gene sequenced from the hare’s blood. The switch regulates the proliferation of the cells which contain the DNA of Beuys’ hare. The amount of peroxide added determines whether the cells will multiply or die. The event at which the piece was auctioned off included a screen with a live ticker showing the current price of staple foods on the commodity exchange alongside bids for the piece. The amount of peroxide added was controlled by the relationship between these two values.

Ironic commentary on the exploding art market

“This biobrick, as we call it, either shrinks or expands depending on the amount of peroxide added. That was also designed to be an ironic commentary on the exploding art market. In our case, the work of art may even back out and refuse to be traded, as if it was no longer willing to play along with the art bubble”, Strecker grins. Having created this project in a period of only two months, Lucie Strecker and Klaus Spiess are interested in the entire process: from the first contacts with the art dealer, the discussions with the conservators on material issues and authorship rights, the talks at the laboratory and the ultimate performance itself. All steps were documented.

Radically open

Strecker's unusual life trajectory can be attributed not only to financial support but even more to her family background. “I am from a family that relates positively to things that are temporary and intuitive. I was free to put my trust in things which may have seemed hard to understand, even to me”, is how the artist describes this environment and she continues: “For me, things do not have to be completely thought through or based on safely anchored concepts in order to deal with them in professional terms and offer them up for discussion.” In her life so far, Lucie Strecker has learned “how important it is to be radically open for something that others, and I myself, may consider as going beyond current standards. When I devote my attention to exactly these things and support them consistently by what I do, a dynamic process starts which will furnish results.”

The unexpected in art and science

Are there similarities to be found here between art and science? In this context, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger spoke of “the unexpected”, meaning that an experimental science set-up is a situation in which certain parameters are defined, but which may give rise to something unanticipated and to new insights. For the unexpected to emerge one needs a protected zone, a zone where experiments can be conducted without social consequences. “In this light, both art and science are protected zones beyond moral arguments, a feature shared by theatre stages and laboratories. Both spheres enable people to exceed boundaries. Afterwards, societal reflection is required. For, what happens beyond these boundaries?” muses Lucie Strecker. The FWF project enables her to pursue such important questions at the interface between art and science.

Born in 1977, Lucie Strecker started professional dance training at the Deutsche Oper Berlin in her early childhood until she decided not to pursue a career as a dancer at the age of 16. She studied art at the Berlin-Weißensee School of Art, thereafter stage directing at the Max Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna and then graduated from her third academic course as a fellow at the Berlin University of the Arts. In addition to many other activities as a teacher and artist, she has been developing and carrying out transdisciplinary performances in the sphere of art and medicine together with the medical professional and artist Klauss Spiess from the Medical University of Vienna since 2009. She has received numerous grants and distinctions and published in journals including Lancet Psychiatry, Performance Research and Diaphanes Publishing. In 2016 her Elise-Richter-PEEK project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF entitled The Performative Biofact at the University of Applied Arts Vienna started in co-operation with the Medical University of Vienna. Lucie Strecker has an eleven-year-old daughter.

More Information

- http://luciestrecker.com/

- FWF programme: Elise-Richter-PEEK